I’m pleased you found The Understory—my biweekly essays with critical perspectives on climate change. If you’re here for the first time, hello! Enter your email below to get issues to your inbox, free.

In Ancient Greek mythology, a meeting was called at Mecone with gods and mortal humans. Prometheus killed a large ox for the occasion and divided it into two piles. In one pile he placed all the meat and most of the fat but obscured the view with the ox’s grotesque stomach atop. In the other pile, he left only bones covered in fat. Prometheus then invited Zeus to choose between the two. Zeus chose the bones, thus leaving all the meat for the mortals. In Hesiod’s telling of the story in Theogony and Works and Days (circa 700 BC), Zeus saw through Prometheus’ trick and chose the bones so he would have an excuse to express his anger on humans. As an act of revenge, Zeus hid fire from humankind so they would suffer in the cold. Prometheus took pity on the humans and stole the fire from the heavens and gave it back to the mortals.

Angered by this act, Zeus promises “great woe for you yourself and for men to come in the form of Pandora,” and instructs Hephaestus to create the first woman out of the Earth. Prometheus’ brother, Epimetheus, marries Pandora who later opens the jar releasing sickness, death, and many other evils on the world. (If you are wondering why we call it “Pandora’s box” instead of “Pandora’s jar,” it is attributed to a mistranslation by Erasmus). But one thing remained concealed in the jar, “elpis,” which has been interpreted by many as “hope.”

The question of why elpis remained in the jar has preoccupied philosophers for millennia. Was hope to be preserved for humankind, or an intention to keep it away from them? Is the jar a prison that locks away hope, or a pantry that stores it ( Apostolos Athanassakis)?

How we answer the question of hope remaining in the jar demonstrates an optimism or pessimism for humankind. Nietzsche believed that by locking away hope, it would keep humankind from being deluded by it. While others have interpreted that by remaining in the jar, hope is always nearby. In “An Introduction to Hesiod’s ‘Works and Days’” published in The Review of Politics (2006), Robert C. Bartlett writes,

“Womankind brings to mortals a certain hope. We are keenly aware of this hope but can never see it realized. Hope almost flew out of the jar and is now just under its lip; hope is as close as possible to being among us without in fact, being so. One might, perhaps, say that we now have hope regarding hope, a condition brought about by Pandora...to speak literally rather than metaphorically: love fills us with the hope that we may conquer the doom or death to which we are born as humans, but it fails to fulfill that hope.”

It seemed very natural to bookend Issue Fourteen on grief with a discussion of hope. I don’t offer hope as a kind of salve to the pains of grieving, nor the assurance that it is going to leap out of Pandora’s jar. Instead, I offer that grief and hope share a similar terrain of action with intention. Both to grieve and to hope conceptualize a changed future—a new story of a reality. Both grief and hope require risk-taking as we orient ourselves to what might be. And it is this uncertainty and possibility about the future that intertwines grief and hope as acts of courage.

Issue Fifteen appropriates Francis Weller’s “terrain of sorrow” to consider the many hills and valleys on the “terrain of hope” to identify how we can cultivate it. When speaking of hope, I want to avoid the desirous false hope that we will have a healthier living planet because we need it to be so. We need not choose between false hope and gratuitous despair. Rather, I would like us to consider what is entailed in our struggle over the future, and what being hopeful means in the context of how we dare to dream, imagine, and live. As Rebecca Solnit notes, hope is not a prize or a gift, but rather earned through the practice of deliberate resistance from the ease of slipping into the state of despair about our future.

Hope is Relational

A semantic distinction is essential before we dive down the rabbit hole of hope. A Rebecca Solnit writes in her treatise on the subject, Hope in the Dark (2004), hope...

“is not the belief that everything was, is, or will be fine. The evidence is all around us of tremendous suffering and tremendous destruction. The hope I'm interested in is about broad perspectives with specific possibilities, ones that invite or demand that we act. It's also not a sunny everything-is-getting-better narrative, though it may be a counter to the everything-is-getting-worse narrative. I could call it an account of complexities and uncertainties, with openings.”

The use of hope as a verb has been casually embraced in our lexicon to express a kind of wishful thinking rarely connected to one’s own active participation such as, “I hope you have a good day.” As Solnit describes, hope as a noun has an entirely different connotation and philosophical lineage. It is this cultivated hope that provides fruitful terrain for how we think about our relationship to a changing climate. In order to avoid such confusion, writers sometimes qualify the word such as “active hope” as written about by Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone.

The meaning of hope can be understood by considering its relationship to bedfellows on the ideological landscape of possibilities such as desire, intention, and optimism. They are all contrivances of our imaginations related to the states of our being and our willingness to alter it. Hope is a compound attitude that consists of two parts. On the one hand, it is the desire for an outcome to occur, i.e., greenhouse gas emissions to go to zero. The other is the intention around a desired outcome, i.e. the motivation to put forth effort to increase the likelihood that zero greenhouse gas emissions will become a reality. Can you hope for something without it being likely to occur? Sure you can. This is what separates hope from optimism. You can be hopeful for something highly unlikely to happen, but should not be optimistic in such circumstances for that would defy reason.

While the Ancient Greeks were more apt to consider hope a pleasure and a result of insufficient knowledge, Plato identified that hope is necessary for human agency. Later Aristotle made the connection between courage and hope, suggesting in the Nicomachean Ethics (circa 340 BC) that every courageous person is hopeful (not vice versa), and “confidence is the mark of a hopeful disposition.” This significance of hope in human agency could be seen nearly 1,500 years later in the writing of Thomas Aquinas (hope incorporates knowledge of the possible and knowledge of the difficulties to reach a desired outcome) and through the 17th and 18th-centuries philosophers with the notable exception of Spinoza. Descartes wrote in Passions of the Soul (1649) that hope was a building block for both boldness and courage (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Generally, even though there are plenty of exceptions, philosophers have regarded hope as essential for courage, bravery, confidence, and boldness. All attributes that we would consider marks of leadership.

The relationship between hope and despair is a repellent one. Charles Eisenstein describes the territory of despair on the vast landscape between hope and the desired destination. Even when we are in the darkest moments of despair, Eisenstein contends that “a spark of hope lies inextinguishable within us, ready to be fanned into flames.” Amnesia, a friend to despair, can root us in a status quo that makes it feel like the only eventuality, which memory repairs. Or even better said by Walter Brueggeman, “memory produces hope in the same way that amnesia produces despair.” This is why we find that in movements centred on hope, an accurate picture of reality and a remembrance of our past are vital to our imaginings of a different future.

Hope Requires Action

For our purposes, the most critical bedfellow to hope is action. In that sense, hope is the beginning, and that is its utility. In the Pedagogy of Hope (1992), Paolo Freire writes,

"Without a minimum of hope, we cannot so much as start the struggle. But without the struggle, hope dissipates, loses its bearings, and turns into hopelessness. And hopelessness can turn into tragic despair. Hence the need for a new kind of education in hope."

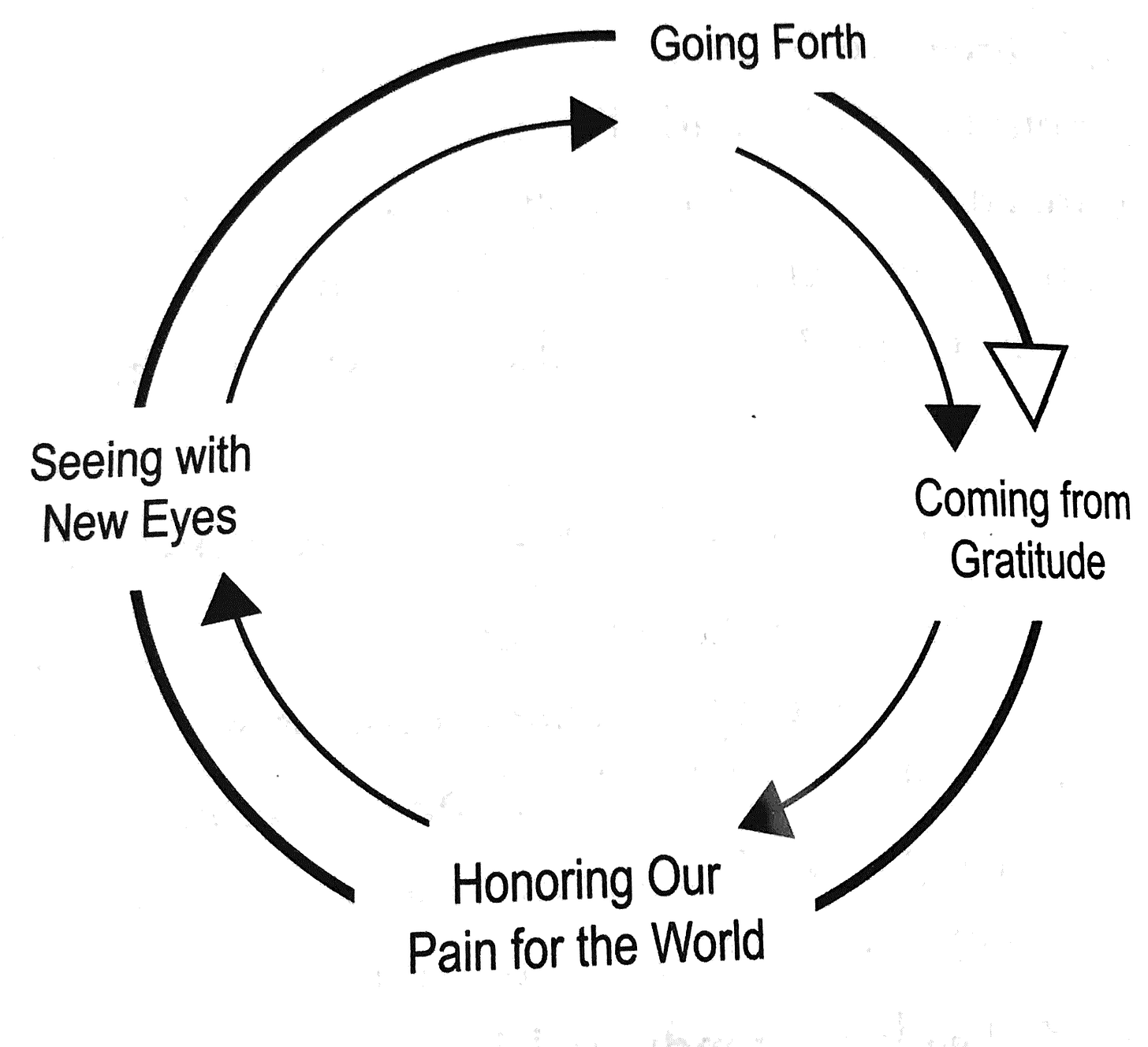

This new education in hope is precisely what Macy and Johnstone sought to provide in Active Hope (2012). Active hope is a practice that “we do rather than have,” with the work in three parts that can be applied to any situation:

Take a clear view of reality (see Issue Fourteen)

Identify our desired outcome

Move in the direction of what we want to see

What is noteworthy for its absence is the arrival at a desired destination. The destination is not a point, but rather the return to refining one’s view of reality that then reinforces the next revolution around the loop. Eduardo Galeano described this idea of utopia in steps: “When I walk two steps, it takes two steps back. I walk ten steps and it is ten steps further away. What is utopia for? It is for this, for walking." If we are to truly embrace the power of hope in our lives, we must embrace the journey rather than the destination. Destination fixation is something that Solnit observed first hand with activists, which became concerning to her about how it leads to burn-out:

“When activists mistake heaven for some goal at which they must arrive, rather than an idea to navigate Earth by, they burn themselves out, or they set up a totalitarian utopia in which others are burned in the flames. Don't mistake a lightbulb for the moon, and don't believe that the moon is useless unless we land on it...The moon is profound except when we land on it. Paradise is not the place in which you arrive but the journey toward it."

The totality of hope and the recognition of the journey therein is perhaps best summarized by the early mission statement put forth by Patrisse Cullors, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter. In her words, the mission of the movement is to “provide hope and inspiration for collective action to build collective power to achieve collective transformation, rooted in grief and rage but pointed towards vision and dreams." It is the relationship of vision and dreams that can next augment how we better understand hope by considering our dreamscapes for an alternative future.

Radical Hope

In The Monkey Wrench Gang (1975), Edward Abbey released a character on the world, George Washington Hayduke III, who would change the eco-activist imagination for decades to come. At first glance, there is little about Hayduke to make one think of him as a hopeful character. He could more easily be mistaken for a nihilist with his irreverence for legal authority and a penchant for drinking more than a dozen beers in a day. Beneath the veneer of Hayduke, Abbey gave us a character whose vision of the world and the boundaries of possibilities were “the wish-fulfillment dream of eco-Luddites everywhere” (Macfarlane). The first paragraph of the chapter introducing Hayduke begins:

“George Washington Hayduke, Vietnam, Special Forces, had a grudge. After two years in the jungle delivering Montagnard babies and dodging helicopters...and another year as a prisoner of the Vietcong, he returned to the American Southwest he had been remembering only to find it no longer what he remembered, no longer the clear and classical desert, the pellucid sky he roamed in his dreams. Someone or something was changing things.”

Hayduke returns disillusioned to find the landscape of the place he once loved, the desert around Tuscon, transformed by humans with the same brute force that had altered the landscapes of Vietnam. Hayduke soon meets up with the other three central characters of the book—Doc Sarvis, “Seldom Seen” Smith, and Bonnie Abbzug—who provide the conversational landscape for their respective perspectives on the state of nature and the imperative for its healthier return. In one such conversation around personal purpose, Hayduke paused for a moment before suggesting, “My job is to save the fucking wilderness. I don’t know anything else worth saving. That’s simple, right?” While the other characters are not as binary in their purpose as Hayduke, they agree to work together to dismantle the “wildlife poisoners”—dams, power lines, bridges, and road-building equipment—laying waste in their view to the beloved canyon country. The biggest of these poisoners on the team’s agenda is the iconic Glen Canyon Dam, the second-highest concrete-arch dam in the U.S., which had removed parts of the Colorado River and created Lake Powell: “storage pond, silt trap, evaporation tank and garbage dispose-all, a 180-mile-long incipient sewage lagoon.” On the current Bureau of Reclamation website, Lake Powell is currently referred to as a “bank account” of water.

For those of you who have not read the book, I will refrain from spoilers. Rather, I’d like to use the note that Abbey left on the opposing page to the Table of Contents as a kind of bridge to what comes next: “This book, though fictional in form, is based strictly on historic fact. Everything in it is real and actually happened. And it all began just one year from today.” In this provocative statement, Abbey invited us to share in his hope for radical environmental action. It only took a few years until a group of environmentalists, led by Dave Foreman, took up the mantle and started Earth First! in 1980. As noted by Robert Macfarlane in The Guardian (2009), “they proclaimed a radical rather [than?] a reform environmentalism, mixing direct action with a kind of guerrilla theatre.” Inspired by Abbey, Earth Firsters unrolled a 300 ft-long piece of black plastic that looked like a crack in the dam from a distance, achieving Hayduke’s dream of demolition at least metaphorically, while chanting, “free the Colorado!”

It is in literature such as The Monkey Wrench Gang where we can discover the imaginings of others, and explore the fruitful terrain of our own hope. As Macfarlane describes, “The Monkey Wrench Gang can usefully help us to think about the ways in which environmental politics might not only be distantly influenced by literature, but in some sense produced by literature." Although Abbey never officially joined Earth First!, he did advocate for their work and was present at the 1981 Glen Canyon action documented in this video.

Click the image above to see the Earth First Action at Glen Canyon Dam & Edward Abbey’s Introduction

Hope as Revolutionary

Activism generates hope by constituting a viable alternative, even if that is only an experimental representation of the desired outcome. In sociology, this is known more formally as the “politics of prefiguration" whereby the means by which the protestors express their desired ends actualizes their own goals. Through Solnit’s writing, I gained a newfound understanding of the Zapatista movement in the Chiapas state of Mexico. It was and remains a movement that strives to be unbounded by our contemporary range of possibilities. They are not choosing between capitalism and socialism. They are unbounded by the relationship (or lack thereof) between spirituality and politics in other communities and nations. They have different conceptions and imaginations for how their social and economic systems should be governed. And they have all of this because they have been antidoctrinal, which Solnit notes has opened them up to new and unexpected alliances and networks of power.

As she notes, revolution aims to fundamentally change the relations of power. This is why the movement is so deliberative in their relationships to remembering their history, as well as to the dreamscapes of hoping for the future that they want to bring forth. This is an important distinction that Manuel Callahan makes about the Zapatistas, as they did not come to “turn back the clock to some lost Indigenous dreamtime but to hasten the arrival of the future.” This is why the rallying cry remains “another world is possible.” But the expression is not enough. Just as with Patrisse Cullors or George Washington Hayduke III, we need to hear what active hope sounds like:

"We Indian peoples have come in order to wind the clock and to thus ensure that the inclusive, tolerant, and plural tomorrow, which is, incidentally, the only tomorrow possible, will arrive. In order to do that, in order for our march to make the clock of humanity march, we Indian peoples have resorted to the art of reading what has not yet been written. Because that is the dream which animates us as Indigenous, as Mexicans, and, above all, as human beings. With our struggle, we are reading the future which has already been sown yesterday, which is being cultivated today, and which can only be reaped if one fights, if, that is, one dreams." Subcomandante Insugrente Marcos

The Zapatistas have been at war with the Mexican government since 1994. They continue to reject and defy political classification. Now we can better understand the hope they have been fighting for all along.

Conclusion

Just like grief, we cannot tackle something we find too depressing to think about. We must first honour the pain of the world through an understanding of actual reality to seed hope for a different climate future. We can then cultivate our own hope for a healthier living planet. As Solnit describes, “hope just means another world may be possible, not promised, not guaranteed.” Hope is a gamble and requires the courage to take a risk. To care about something deeply enough to help bring it about in the world. To be confident in our journey to relish the path rather than the destination. We cultivate hope by doing rather than having.

Somewhere, Pandora’s jar remains tightly shut. Enclosed, but near the rim, rests hope for all of humanity. It sits alone, having been freed from all the ills and evils of this world. As Abbey says, "everything in it is real and actually happened. And it all began just one year from today.” Consider that your invitation to cultivate hope.

Go forth and make a difference in the week ahead.

Adam

In between issues I share my own reflections and those I have heard from readers. While the term community is often overused and thus abused, The Understory is a community of readers who value the comments of others. Please reply to this email or leave a comment on the website with any reflections you feel comfortable sharing 🙏.

If you liked this issue, please subscribe. The Understory is free and will come to your inbox weekly.

Why I Write The Understory

We have crossed the climate-change threshold from emerging to urgent, which demands a transformative response. The scale of the issue demands not only continuous focus but also the courage to take bold action. I've found that a persistence of climate consciousness improves resilience to the noise and distractions of daily life in service of a bigger (and most of the time invisible) long-term cause.

The Understory is my way of organizing the natural and human-made curiosities that capture my attention. Within the words, research, and actions of others lies the inspiration for personal and organizational journeys. I hope that my work here will help to inform not just my persistent consciousness, but yours as well.

I can't help but reflect that the word "hope" in French has two translations "espoir" and "esperance" giving the nuances of dream vs. active hope that you touch on, and that the latter translation shares the same root with the word "aspiration", one of Dr. Lertzman's three As - Anxiety, Ambivalence and Aspiration. Furthermore, while you could "perdre espoir" i.e. lose hope, become hopeless, you cannot lose "esperance". So again this is the brilliance of Joanna Macy's progressive narrative of the Great Turning, reclaiming this time as a New Beginning.

Thank you for such a thoughtful and rich essay! There is so much here to unpack. I wanted to share a couple of links on this theme that resonate:

A few years ago, I wrote about blowing up the hope/despair binary for Sierra: https://www.sierraclub.org/sierra/how-can-we-talk-about-global-warming

And more recently, this New Yorker essay touches on the theme: https://www.newyorker.com/science/elements/the-other-kind-of-climate-denialism