I’m pleased you found The Understory—my biweekly essays on consciousness during the climate emergency. If you’re here for the first time, hello! Enter your email below to get subsequent issues in your inbox for free.

“The coming awakening stands like the wooden horse of the Greeks in the Troy of dreams.” Walter Benjamin

Eschewing the adage to never judge a book by its cover, I’ve always found that the best book cover designs are invitations to uncover what lies below their illusions of simplicity. The cover of the first hardback edition of The Overstory is striped with nine different colour bands, each showing a different tree. This visible layer of this design on one level represents the initial vision Richard Powers envisioned for the book—one in which trees were the central characters.

The Overstory is a book about trees and Tree. That alone is likely not a spoiler. However, if you have not yet read the book, please be forewarned that this essay does not shy away from details that are likely to change your reading of the novel. Within each of the cover’s nine individual trees resides a character story of someone whose corporeal relationship to Tree transforms their consciousness. There is Dorothy who forms a relationship with a linden when she crashes her car into it. Neelay who falls from one of the branches of a sinuous oak rendering him a paraplegic. Douglas whose life is saved by a sprawling, sacred Thai 300-year-old banyan tree “bigger than some villages” with three hundred main trunks and two thousand minor ones that catches his skyfall after his C-130 is shot down. Olivia and Nick who transport their bodies hundreds of feet above ground into the canopy of Mima to live for months at a time.

Like a prism that separates white light into its component colours, trees disperse and connect the living world into a complex whole. The Overstory is neither a novel of people nor of trees, but rather the quest to find a new equilibrium that puts human and the more-than-human world on a balanced plane that reflects our entwinement. The cover design by Glenn O’Neill acknowledges that to tell the human story we need to bring trees and the larger non-human world into the foreground. O’Neill’s cover for Powers’ narrative invites us to learn to see the white light and its refracted colours.

From day one I’ve openly acknowledged that Richard Powers’ great novel inspired me to start writing The Understory. My publication name is a tribute to the book, as is the underlying thread of interconnectedness that runs through many issues. Until recently it had not occurred to me to dedicate an entire issue to the book despite my adoration for it. It was in hearing and reading a series of interviews with Powers that awakened me to the wonderful synchronicity of the novel’s nine characters with Powers’ shifting consciousness in writing them. A few years after my first read of The Overstory, I now see the novel first and foremost as a conversion story—from one of individuated human separation to one of interconnectedness in living systems. This is fruitful terrain for The Understory after all.

Issue Twenty-Eight is a space to attend to Powers’ myriad voices about what a planetary consciousness sounds like and what the journey entails towards a deeper climate response. Two years before Powers publishes The Overstory, Amitav Ghosh asks the central question in The Great Derangement: Climate Change and the Unthinkable: “Why does climate change cast a much smaller shadow on literature than it does on the world?” In The Guardian essay, Ghosh argues that the challenge of writing about climate change is that it demands the author to imagine a way out of our current crisis of culture. Perhaps Powers heeded Ghosh’s call (as have many others cited in previous Understory issues), recognizing that what is most needed in our current moment is a bridge across cultural divides whose span takes us from the shores of unregulated capitalism, extraction, and growth to the far shore of atonement, interconnectedness, and sufficiency. The Overstory narrates the conversion experiences of a planetary consciousness that charts a path out of our current climate emergency not through electric vehicles and carbon-sucking turbines but rather by collectively awakening to the life-supporting systems that surround us and our integration rather than separation for them. Issue Twenty-Eight seeks to linger on that far shore for a while in hope of bringing it closer. To unfold the stories of awakening and conversion at the speed of trees.

Binding Worlds

“The best arguments in the world won’t change a person’s mind. The only thing that can do that is a good story.” Adam, The Overstory

In an interview with poet Forrest Gander, Powers describes a kind of intentional rebalancing of the human and nature narrative:

“I didn’t want to tell a story that was exclusively about trees any more than I wanted to write another novel that was exclusively about people. I mean if the whole point of breaking down human exceptionalism is to say there is no separate thing called us, and no separate thing called wilderness, then I needed a forum where these protagonists could be on an equal footing. That required certain inventions and plot points that allow for radical re-focalization.

The Overstory is a direct attempt to break through the kinds of distortions and illusions (see Issue Sixteen) that are blind to ecological value in the face of economic, political, and scientific rationalization. The equal-footing that Powers seeks is not stories of equality amongst humans but rather an equalizing of humans as components rather than extractors of complex living systems. The socio-cultural systems in the novel deliberately parallel the reality of our current systems. The Life Defense Force protest camp has its historical roots with the Redwood Summer in Humboldt County in 1990 when loggers and protestors staged a three-month standoff which foreshadowed the ongoing old-growth protests still taking place at Fairy Creek on Vancouver Island (hooray for the recent victory!) with nearly 1,100 people arrested and the Trans Mountain pipeline protests just minutes away from where I live. The redwood forests Nicholas looks across are indeed owned by a financier who has never visited them and only seeks the highest returns to recoup personal debt used to acquire them as Powers suggests. And we know from the personal account of Suzanne Simard in Finding the Mother Tree that the North American foresters fought red in tooth and claw to deny the science that old trees ensure the healthier growth of new ones, that mixing species results in more resilient forests, and that a healthy understory creates thriving rather than competitive conditions for new trees.

The culmination of our socio-cultural condition is perhaps most comprehensively addressed in the character and story of Neelay Mehta. While rolling around the Stanford inner quad going "from planter to planter, touching the beings, smelling them, listening to their rustles." Neelay has a vision:

“What the boy wanted the black box to do was innocent enough: to return him to the days of myth and origin, when all the places a person could reach were green and pliant, and life might still be anything at all...There will be a game, a billion times richer than anything yet made, to be played by countless people around the world at the same time. And Neelay must bring it into being. He'll unfold the creation in gradual, evolutionary stages, over the course of decades. The game will put its players smack in the middle of a living, breathing, seething, animist world filled with millions of different species, a world desperately in need of the players' help. And the goal of the game will be to figure out what the new and desperate world wants from you...And down in the cool riparian corridors smelling of silt and decaying needles, redwoods work a plan that will take a thousand years to realize—the plan that now uses him, although he thinks it's his." Neelay Mehta, The Overstory

Throughout the novel we follow Neelay’s journey as the manifestation of our contemporary virtual-world building and planetary exploring entrepreneurs. Neelay’s game, Mastery, and its many iterations endow players with God-like creation privileges with responsibility for its stewardship. In what seems like a perverse logic—teaching players concepts of interconnectedness and reciprocity living within a digital world rather than the real one—Powers invites us to consider the dialectic of technology. Has the science of ecology and the ability to understand complex systems through computation and digital models brought us closer to or further away from the living world? In “Kinship, Community & Consciousness,” Powers asks us to consider whether we should become more reliant on technology to recover the non-technological:

“Will we double down on the great migration into symbol space, our decampment into Facebook and Instagram and Netflix and World of Warcraft, the road that we have already traveled so far down? Or will Big Data and Deep Learning allow us to grasp and rejoin the staggeringly complex processes of the living world? The two possibilities are not mutually exclusive. Indeed, they’re inseparable aspects of the new ecology of digital life. It’s surprising to realize that the rise of ecological and environmental consciousness was made possible by the advent of the Information Age. Life is simply too complex and interdependent for us to wrap our heads around without the help of our machine prosthetics. And now those prosthetics allow us to assemble, generate, contemplate, and interpret the hockey-stick graphs that prophesy our future. We came into being by the grace of trees. Now the fate of trees, and of the whole world forest, is squarely in our machine-amplified hands.”

Neelay’s story reflects a contemporary mythological parable. The very technologies that separated the living world into constituent parts and endows humanity with a sense of separation might become the very prostheses that reveal new pathways to returning to what we have destroyed and once known in piecing the world back together. As Ghosh identities, treating what is happening to our living planet as purely mythological neglects its urgency and actual harm.

“This is the question that the core group of would-be tree-savers in my novel must stare down, both on the ground, in the face of bulldozers and feller-bunchers, and two hundred feet in the air, camped out in the incredible canopy ecosystem of the giant coastal redwood, Mima. How much are we compelled to give to a cause that may already be lost? Does it matter that you save the last few acres of virgin forest, if 98 percent of it is already cut? When does practicality and reason start becoming the enemy of sanity, and vice versa? What is the use of resorting to tactics that are likely to lose the hearts and minds of the public without doing much more than annoy the clear-cutters and cause them to speed up the project of human mastery over everything else alive?” (“Here’s to Unsuicide: An Interview with Richard Powers,” Los Angeles Review of Books)

It is hard to enjoy many of the moments in The Overstory while bereft with pain and trauma. Yet Powers understands that we have to face our contemporary systems of conflicting values to resolve this crisis of cultural separation at the root of our climactic moment. “What we can’t bring about in no way changes what we must bring about,” notes Powers on the imperative of narrative to bind worlds back together when there seem to be so many conflating forces trying to tear them apart.

A Novel of Response-ability

The Overstory is a return to the realist novel of the 19th-century which seeks to paint a rich picture of a complex, real world and asks the reader how they might navigate it with their morals and values. This choice is a direct confrontation by Powers to the delusional form that many contemporary novels take by either reifying existing structures of capitalist harm or ignoring the address of them altogether in service of a more “entertaining” read. A culture of accumulation through extraction and dispossession (David Harvey) has social and planetary consequences. In speaking to The New York Times, Powers summarizes the central question of The Overstory as "why are we so lost and how can we possibly get back?"

Powers believes that society (and its cultural corollary in fiction) has largely been on a wayward journey over the past century. In his remarks to Forrest Gander, he notes that we’ve largely stopped telling the story of man against the elements because of a certitude that we had won the war against the more than human world: “It wasn't a drama anymore because we were in charge.” While novels used to predominately integrate three-levels of conflict, contemporary novels often limit their purview to the psychological battles within a person and/or social/political battles between people:

“There’s a paradox here. While the challenge to our continued existence on Earth has never been greater or clearer, literary fiction seems to be retrenching into an obsession with the challenges of private hopes, fears, and desires. Granted, those challenges lie at the heart of everything we try to do, but a retreat into belles-lettres when human activity is unravelling the climate, exhausting the soil, and killing off 40 percent of the world’s other species is simply reactionary solipsism. We need level-three stories and myths, and we need lots of them fast, in all kinds of forms and flavors.” (Los Angeles Review of Books)

Continuing to centre stories on human fates and choices (what Powers describes as “commodity-individualism”) deepens our sensibilities that humans are the centre of Universe. He deliberately dissolves characters and their private narratives into a web of interconnections with others and the more than human world. The struggle to preserve the ancient forests throughout the book can be seen as a willingness to sacrifice the individual for the collective, and the human species for the more-than-human world into a consequential system of reciprocity. These characters do not become martyrs but rather conscious and willing bystanders to larger forces at play in which they offer themselves.

Powers’ narrative strategy does not seek to undermine the importance of individual action, but rather to contextualize it within larger systems beyond our own self-importance. Powers describes his desire to “yank them [his characters] out of that sense of a purely personal and synthetic and invented meaning...and force them to take the place that they’re living in as something alive” (“Kinship, Community, and Consciousness,” Emergence Magazine). There is a powerful distinction at play that Powers draws between being responsible individuals and learning “how to respond and ‘opening up possibilities for different kinds of responses’” in what Martha Kenney describes in “Fables of Response-ability: Feminist Science Studies as Didactic Literature” as the kind of moral and ethical living required to navigate the more-than-human world.

While not mentioning The Overstory directly, Kenney writes of stories that are “fables of attention, texts that teach us to pay attention to our world in new ways.” She quotes Thomas Keenan’s further elaboration about these types of stories: “What is at stake in the fable is, more than anything else, the interpretation and practice of responsibility—our exposure to calls, others, and the names with which we are constituted and which put us into question.”

One of the most vivid examples Kenney offers of this type of storytelling is Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring which opens with the first chapter “A Fable for Tomorrow” and the framing question, “What has already silenced the voices of spring in countless towns in America?” Through this work Carson changes not just our understanding of agrochemicals and our bodies, but even more importantly that these are shared vulnerabilities between the human and the more-than-human world that connect us. Poisoning our soils with chemicals destroys Life. Carson’s writing “makes relations sensible,” which cultivates the capacity of her readers to respond (evidence being the cascade of the strongest bipartisan legislation in U.S. history protecting non-human life)—catalyzing what Kenney and Donna Haraway describe as “response-ability.” By drawing us into new “economies of attention,” fables such as Silent Spring change what we notice and how we respond. Kenney writes:

“We need to continue asking what kinds of stories, academic or otherwise, can help us account for everyday environmental violence in ways that engender meaningful, collective response in many forms: as policy, as activism, as pedagogy, as care, as knowledge-making, and as the intimate practices of everyday life.”

Through the nine character studies in The Overstory, Powers cultivates our capacity to respond. He does this not by being prescriptive but rather by manifesting myriad possible contributions by each one of us. Powers knits together a Universe of relations. The novel endows response-ability by binding these worlds together in ways that cultivate our ability to respond.

Metamorphosis

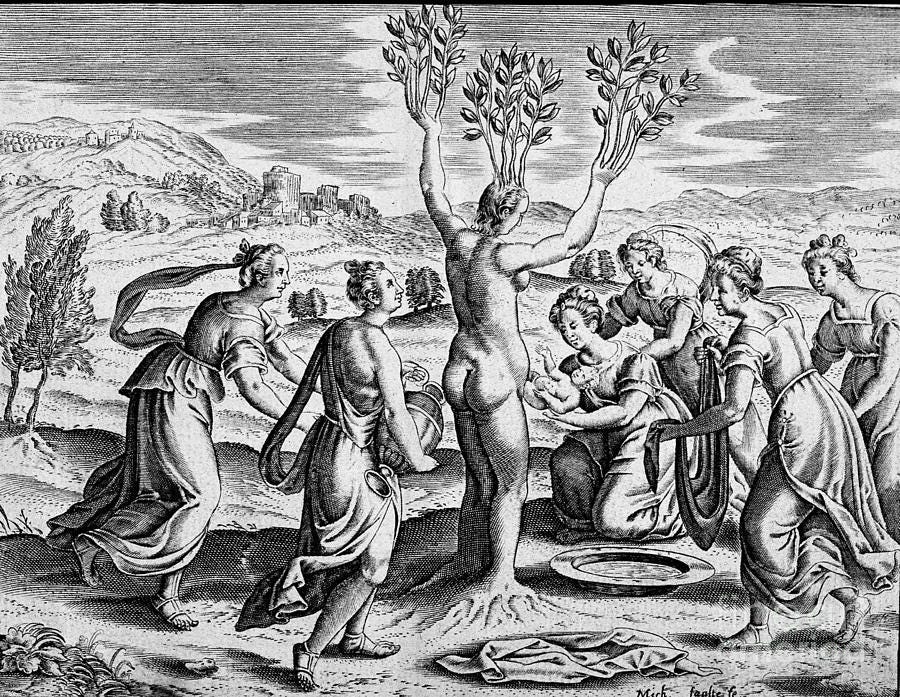

“‘Let me sing to you now, about how people turn into other things.’ At those words, she's back where acorns are a step away from faces and pine cones compose the bodies of angels. She reads the book. The stories are odd and fluid, as old as humankind. They're somehow familiar, as if she were born knowing them. The fables seem to be less about people turning into other living things than about other living things somehow reabsorbing, at the moment of greatest danger, the wildness inside people that never really went away...She loves best the stories where people change into trees. Daphne, transformed into a bay laurel just before Apollo can catch and harm her. The women killers of Orpheus, held fast by the earth, watching their toes turn into roots and their legs into woody trunks. She reads of the boy Cyrparisus, whom Apollo converts into a cypress so that he might grieve forever for his slain pet deer. The girl turns beet-, cherry-, apple-red at the story of Myrrha, changed into a myrtle after creeping into her father's bed. And she cries at that steadfast couple, Baucis and Philemon, spending the centuries together as oak and linden, their reward for taking in strangers who turned out to be gods.”

This evocative opening line about transformation from the children’s translated version of Ovid’s Metamorphoses (AD 3-8) is what greets Patricia Westford as she opens the book on her fourteenth birthday—foreshadowing her own transformation and those of The Overstory’s protagonists. Powers speaks of the Metamorophisis as being central to the organization of his novel. He reveres Ovid’s ability to transcend the human-exceptionalist narrative through direct kinship with other living beings (Emergence), and how stories of becoming open gateways into an expanded consciousness: “We can open that consciousness to the knocks of strangers so very unlike us, or we can close the doors and go back inside. Either way, as the old Ovidian song says, a change is gonna come” (Los Angeles Review of Books).

Unlike Ovid’s stories of physiological metamorphosis of humans into over 100 other living things, The Overstory’s transformations are largely (but not exclusively) psychological. Powers leaves their corporeal transformations to the imagination: “PEOPLE TURN INTO OTHER THINGS.”

“Fogs from the world's infancy turn the clock back eons, and he feels himself becoming another species.” Nick’s reflection from the crown of Mima, The Overstory

The redwoods protest camp is a symbolic stand-off between two worlds: that of the mythological with intertwined kinship between all species and that of the exceptional where other living species in service of human dominion. The kinship of the protest camp takes such a hold on The Overstory characters that they find themselves unable to return to lives lived before the camp—as one battle is lost, they seek out the next one in another forest. The characters embark on a singular narrative of protection where place becomes the demonstration of the interconnection of all planetary life rather than of singular distinction to a particular forest or tree—another instance of Powers’ reverence for the collective.

Powers’ personal departure first into the mountains above Stanford and eventually to live in the Great Smoky Mountain of Tennessee and then into the characters of The Overstory is a stunning evocation of the relationship between inner and outer transformation. Through the practice of writing The Overstory, Powers finds himself not able to go back and write novels like he used to. His desire becomes to deepen the stories of kinship that he started with The Overstory in subsequent novels rather than hopping subjects from novel to novel. True to his conviction, Powers’ thirteenth novel, Bewilderment, was published last week, which critics describe as a continuation of The Overstory rather than a new starting over as the author did in his subsequent twelve novels.

“This is my twelfth novel—I’ve been writing novels for over a third of a century. It’s the first novel that ever moved me across the country and literally changed my life in terms of what I do all day long, how I live, and where I live...In order to escape that sense of mastery and control—a future in which all things would be managed to our benefit—I would disappear for longer and longer periods of time up into the trails of the Central Peninsula, and the Santa Cruz Mountains, and into the long past...It became clear to me that Silicon Valley was down there because these redwoods were up here, and the story that we tell about the technological transformation of the world—in which we are the central, sole heroes—was not actually telling the whole story, the whole truth...I began to feel like the journey is so profoundly imbricated and knotted together that my own destiny and the destiny of these other things were not anywhere near as separate as I thought they were when I started the journey. So, did I become smaller and more vulnerable? Yes, but I also became larger. In a Whitmanesque way, I started to contain multitudes, or they started to contain me. ” (Emergence)

Powers awakens to the realization that his literary practices and subjects have become commodified production. Walter Benjamin referred to this as the dream state of society that needs a collective awakening (“Dreaming of the Collective Awakening,” Warren S. Goldstein), of which Powers forms a microcosmic collective—personally and within his narrative worlds. Writing The Overstory became Powers’ conversion not just into a different way of seeing, but into an entirely different way of being in the world. Powers transitioned from a daily threshold of a thousand words to four miles—a transposition of markers that brought him into presence with the living world as his requirement for a fulfilling day. “Now, I wake up, and I go outside on the deck, and I say, ‘What is it doing out there? What are my possibilities for discovery and connection?’”

What Powers describes both personally and in his characters is a conversion not unlike the religious conversion experiences mythologized in the world’s sacred texts. Trees are “imbricated and knotted together” in many of the most iconic, transcendent moments of cultural awakening. The Buddha is said to have achieved enlightenment sitting under a Bodhi tree in India (the same type that saves Douglas). On his travels from Mecca to Syria at the age of twelve, the Prophet Muhammad is said to have stopped to rest under a lean and leafless Sahabi tree which became filled with green leaves to provide shade. Saint Augustine of Hippo shares in poetic prose across many pages his conversion experience to Christianity in Confessions—depicted by Fra Angelico with Augustine sitting and weeping under a tree. If we have become acculturated to trees being the hosts and shelter for personal conversion experiences in religious narratives, could they also not serve the same value for spiritual transformation?

“Tree consciousness is a religion of life, a kind of bio-pantheism. My characters are willing to entertain a telos in living things that scientific empiricism shies away from. Life wants something from us. The trees say to each of these people: There’s something you need to hear...That’s why The Overstory is swarming with Greek and Egyptian and pagan European and Indian and Chinese and Indigenous American myths about trees. It’s trying to resurrect a very old form of tree consciousness, a religion of attention and accommodation [emphasis added], a pantheism of sorts that credits other forms of life—indeed, the life-process as a whole—with wanting something.” (Los Angeles Review of Books)

The Overstory turns our gaze upwards and all around, and then confronts us with the limitations of our imagination and the responsibilities that ensue from an expanded one. As Nick notes when speaking to a curious logger about what it is like to live hundreds of feet above ground in an old-growth tree that his career has been spent cutting down—there are thickets of huckleberries up there. The logger asks, “And a pool with fish in it?” Nick replies, “there’s more.”

In Issue Twenty-Two we addressed the question of whether the climate movement, like the world’s dominant religions, could instill non-negotiable, sacred values that might transform the way we act in the world based on our moral beliefs. In the essay, Robert Bellah shares that narrative, images, and enactment are ingredients that can be co-opted towards the same ends as religion. Looking back on this idea six issues later and two years after my initial reading, I realize why The Overstory is so much more than a novel. How the book became a conversion experience for me, Powers, and so many others. Similar to a religious text, The Overstory is a “fable of response-ability” that uses narrative, images, and enactment to cultivate our capacity for climate response (Kenney). Just as Amitav Ghosh prescribes, The Overstory imagines a way out of our current crisis of culture through conversion in the canopy.

“A chorus of living wood sings to the woman: If your mind were only a slightly greener thing, we'd drown you in meaning.” The Overstory

Conclusion

“The pine she leans against says: Listen. There’s something you need to hear.”

Richard Powers seeks to answer the question in The Overstory “why were are so lost and how can we possibly get back?" He shares an answer succinctly in a conversation with the author David Abram: “What I wanted to do was in one volume say that there is a narrative that binds these two seemingly different modes of existence into a social, communal, networked, reciprocal, and interdependent changing dynamic whole.” The two modes of existence Powers refers to are the human and the more-than-human worlds. Across five hundred pages, he interweaves a narrative of shared vulnerabilities and symbiosis between species that our economic and dominant cultural narratives have sought to subsume beneath layers of toxic topsoil, acidifying oceans, drought-covered landscapes, and carbon-intensive skies. Despite the marketing engines working at full bore to prove the contrary, we are awakening to the trauma of what an unbalanced ecology looks like where human are neither in charge, nor seemingly willing to be courageous enough to alter the destiny of our shared future.

The Overstory is not just a seminal novel for our cultural moment, but also a return to the largely abandoned form of the 19th-century realist novel. What Powers achieves is a layering of response-ability that increases our collective capacity to act. The novel is an expansive, narrative space that reorients our attention. Here we learn to listen to different voices. And while those voices diverge in myriad responses, they unite in collective action and consciousness. “Awe and wonder are the first, most basic tools involved in turning toward and becoming attentive to that meaning above and beyond our own,” says Powers (Los Angeles Review of Books). If we don’t attend to the meaning of the interconnectedness of the living world human meaning will come to mean very little. Thanks to The Overstory and other great works of consciousness building, we are cultivating our capacity to listen with response-ability.

“All the drama of the world is gathering underground—massed symphonic choruses that Patricia means to hear before she dies.” The Overstory

“This will never end—what we have. Right?” Olivia, The Overstory

Go forth and make a difference in the week ahead.

Adam

In between issues I share my own reflections and those I have heard from readers. While the term community is often overused and thus abused, The Understory is a community of readers who value the comments of others. Please reply to this email or leave a comment on the website with any reflections you feel comfortable sharing 🙏.

If you liked this Issue, please subscribe. The Understory is free and will come to your inbox weekly.

Why I Write The Understory

We have crossed the climate-change threshold from emerging to urgent, which demands a transformative response. The scale of the issue demands not only continuous focus but also the courage to take bold action. I've found that the persistence of climate consciousness improves resilience to the noise and distractions of daily life in service of a bigger (and most of the time invisible) long-term cause.

The Understory is my way of organizing the natural and human-made curiosities that capture my attention. Within the words, research, and actions of others lies the inspiration for personal and organizational journeys. I hope that my work here will help to inform not just my persistent consciousness, but yours as well.

OMG! I loved The Overstory and similarly found it love changing in that I look at a trees completely differently, as wise old friends. I notice them and care for them and grieve for each one lost in our neighbourhood whether due to development or erosion or climate change such as this summer’s drought and intense heat. I have also read many of the same books and many about the magical mycelium that also lies magically beneath us.

I often wondered if the Overstory was the inspiration for the Understory. I am thankful for both.

Every time I read your parting comment “go forth and make a difference this week” I am in awe of how much you make a difference through education and reach and the complex discussion. Maybe that is a good place for all of us to start. And maybe this book is just one of the many catalysts to the movement. The more people we can convert, the closer we will get to action.

Yes to this: "what is most needed in our current moment is a bridge across cultural divides whose span takes us from the shores of unfettered capitalism, imperialism, and growth to the far shore of atonement, interconnectedness, and sufficiency. " Thank you as always for such eloquent and evocative writing, and for the clarion call for each of us to engage as deeply as we may be capable in these questions and this conscious evolutionary journey.

My current read is Glenn Edney's The Ocean Is Alive. Having listened to his interview on Manda Scott's excellent Accidental Gods podcast ( https://accidentalgods.life/the-ocean-is-alive/ ), I hunted up the book and have spent two weekends absorbing his extraordinary weaving of the breath and circulation of our very planet herself. Another exemplary human in the circle of Schumacher College, he works from the Gaia hypothesis and all that it implies, while also assembling and contributing rich additional data to continue support for that hypothesis - through both detailed scientific observation and through direct experience of that observer.

What he told me yesterday in our conversation left me considering each of our roles. He had been speaking with Master Herbalist Stephen Harold Buhner about the strains of trying to bridge the gap between his experience and vision of Gaia, and those who have yet to grasp that reality. Buhner said, simply: "You can choose to be a bridge if you want. But the problem with being a bridge is that you are there in the middle, carrying a burden, and that burden can get heavier and heavier until you collapse. But you have already heard the gorgeous choir singing on the other shore. Why not join that choir, add your voice to that choir. In that case, your only job is to insure that your voice raises the beauty and volume of the call. Those who are open to that call will find their way to the other shore."

Here's to those, like you Adam, who act in some ways in both capacities. We dash back and forth, singing mightily on the other shore at times, while also coming back and guiding the way with torches in the darkness.