I’m pleased you found The Understory—my monthly essays on consciousness during myriad social and planetary health crises. If you’re here for the first time, hello! Enter your email below to get subsequent issues in your inbox for free.

After finishing the last issue, “Recalling the Amnesiac,” I felt unresolved. While I made a decently effective case for the urgency of retrieval with an eye towards a plurality of knowledges, I hadn’t yet centred the challenge on our (in)ability to deeply imagine. While many of us can see the undesirability of the dimensions of our present and how that is leading us on a crash course with a fatalistic future, that future-presenting is not the same as understanding a different civilization. Have we overly preconfigured and therefore limited our imaginations of potential futures? The expansiveness or limitations of our imaginings determine the direction of travel—whether one of step-change iteration or embracing transition on the way to true civilizational transformation.

As I was researching this Issue, my wife rediscovered an illustration our daughter made in primary school (she’s now fifteen and would likely not be all too pleased I am sharing it) in the ever-accumulating parental archives. The assignment was an imagining space of trying to illustrate a somewhat distant past and what might be the emerging future.

I found myself proud on the one hand that our daughter was familiar with the Indigenous identification of North America as Turtle Island. While she did interpret that idea quite literally with turtle flags and turtles swimming around, she was clearly trying to reconcile a past with a discontiguous future. What I found so helpful about my daughter’s imaginings is not that they are hers, but rather a reflection of the dominant worldview that many of us continuously reinforce despite quite clear evidence to the contrary. My daughter envisioned the past as beautiful, filled with nature, and peaceful. Things were traded within and between Indigenous nations rather than bought or sold, which means she began to comprehend that there were once indeed quite different forms of social arrangement. Said humans are visually absent in the landscape other than their material contributions of a dwelling and flag, perhaps busily living their pre-colonial lives off the page. As it was a time “before it was destroyed” by the Europeans, the oceans were not yet laden with microplastic; the air was not filled with 415 ppm of carbon dioxide; and seemingly everyone had sufficient provisions to maintain a peaceful society.

The second panel of my daughter’s illustration is her vision of the future. It’s noteworthy that annotations are absent; instead, she simplified the imagining to an industrial scaling of the built environment. A street lamp is a stand-in for the sun which has been obscured by buildings. The only visible text of the future other than addresses on buildings is an advertisement soliciting consumption. The level of detail our daughter envisioned for future civilization was less replete than her imagined past. It would be overly simplistic to chalk this up to age, as it's highly likely people decades older would face similar time struggles. Are we challenged to personally and collectively imagine futures? If so, what are the implications for our decisions and behaviours in the present?

My evocation of this primary school illustration is not to critically analyze a seven-year-old’s worldview or art skills, but rather to make concrete the colonization of our own imaginations from a very young age in the attempt to better understand the lengths required to decolonize what has been deeply nested within. Much like the unceded territories in which many of us live, we did not accept an invitation to colonize our imaginations. And yet here we are—western nations primarily composed of colonists endowed with self-perpetuating mechanisms of justification and further colonization. Histories are erased for us, and thus the work becomes the process of un-forgetting that which most of us have never actively known in the first place. This is not to suggest that decolonized imaginations are the endpoint to solutions for our myriad systemic crises, but rather the starting point for real possibilities of transition.

Judging by social media feeds and media headlines, we seem to have dozens of ways of abstractly conjuring the idea of a different future through short-hand expressions like a better planetary future, a civilization where everyone flourishes, and a more sustainable world. These vague clarion calls have inspired a series of questions that I will discuss in this essay.

What is this so-called better future that we envision?

Do those visions share more than a lexicon and the actual vision of what it will take to achieve them?

Are we creating the spaces to incubate heterogenous futures where many worlds fit or are we carrying forward the homogeneity of a globalized colonial mindset of a singular future?

If we recognize both a vague vision of the future and the importance of having a more replete one, can we prioritize the processes of decolonizing our imagination as productive to carve off the time and space from task-level living and overconsumption?

If we are to move from the general to the specific, it demands a series of reckonings about what in particular we seek to retrieve, what we are willing to leave behind, and what we are willing to create and support anew?

Over the past few months, I’ve spent time with writers whose primary intentions are dislodging tidy grand narratives with the recognition that those so-called better futures can only be achieved through pluralism. Shiv Visvanathan, Tim Jackson, David Graeber, David Wengrow, Alexis Shotwell, and Arturo Escobar help us to consider the continuous process of retrieving pasts—the process of unforgetting—so that our future-present is shaped by decolonized imaginings. While quite divergent, their writing shares many commonalities that combine epistemological (knowing) and ontological (being) shifts. In Against Purity: Living Ethically in Compromised Times (2016), Alexis Shotwell weightily summarizes the paradox each of these authors writes into:

“How do we craft a practice for imagining and living a future that does not simply replicate and intensify the present?...We cannot look directly at the past because we cannot imagine what it would mean to live responsibly toward it. We yearn for different futures, but we can’t imagine how to get there from here. We’re hypocrites, maybe, but that derogation doesn’t encompass the nature of the problem that complexity poses for us.”

Issue Thirty-One attempts to elevate the importance of imaginings and widen the lens of possible futures as we courageously look back and ahead. We’ll take the long road rather than the shortcut with sage guides to prepare ourselves for generative imaginings. Together we can open the process of myriad becomings—not delimited by the rationalizations and vulgarities of our pasts— but rather the desires of a rethought civilizational future. By recognizing that that elusive better world that sits out there on some distant horizon cannot be reached from here, we are forced to reconcile that which we must let go of to open ourselves up to what in hindsight will be recognized as true betterment. A future without the transition into an ecologically safe and just space for all life is a failure of the personal and collective imagination.

Against Purity (Or Being Contiguous With Everything on Earth)

A common trope of spy narratives is the transition from the uncompromised state of being to the compromised state of the secret agent. After observing the spy navigate worlds in a state of pure deception to those around them, eventually the switch gets flipped and the agent’s true identity and intentions become exposed. Technically known as being “burned,” this state change results in cascading networks effects for the others that are connected to them, the nations that have supported their espionage, and often broad-scale civilizational catastrophe involving nuclear weapons, biological agents, or other worldmaking cataclysms.

Now I ask you to imagine a different starting point to the story in which the agent’s true identity is known to all from the beginning. The protagonist is acknowledged for who they are and thus a dramatically different narrative might ensue. After all, there would be no cascading network effects because the deceptions never were realized. What was once a thriller based on deception now opens up other narrative possibilities. Is it to become a story of redemption? Of self-discovery? A love affair?

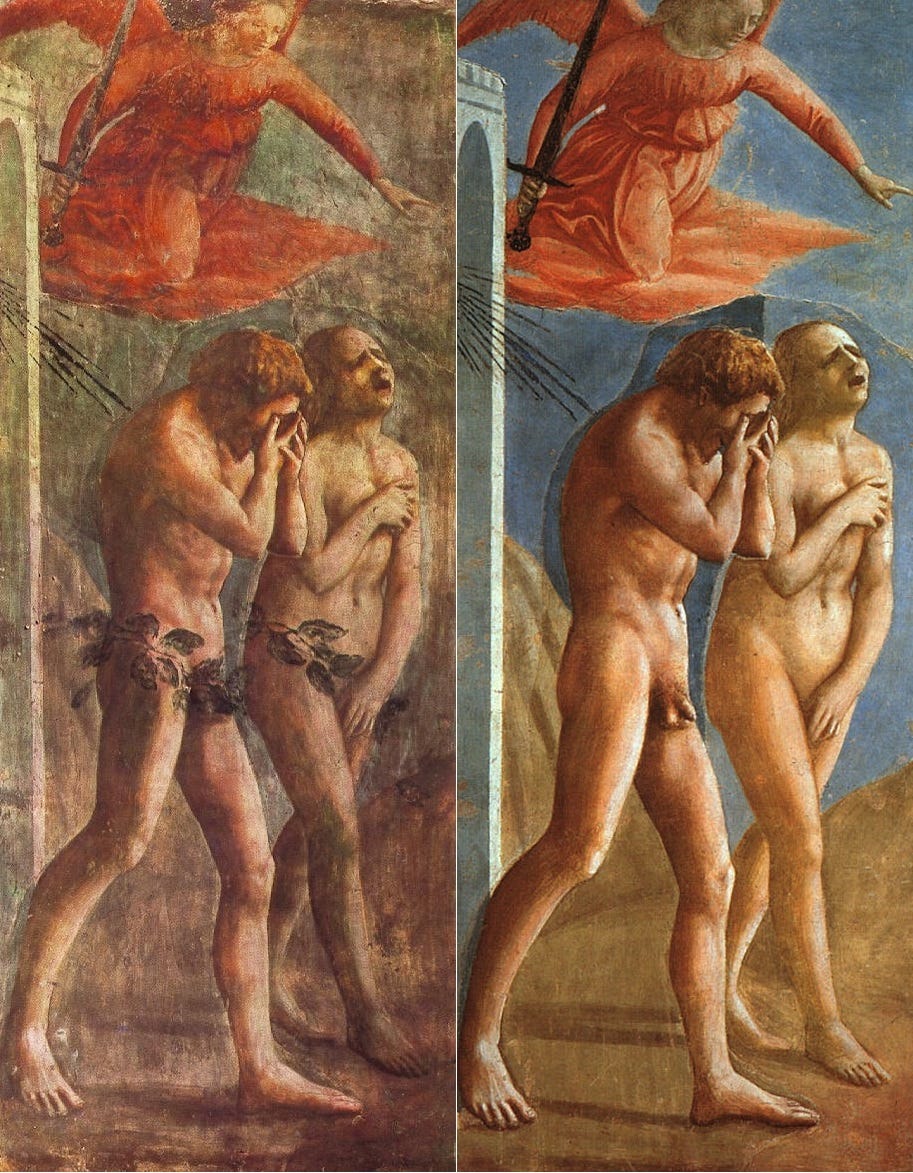

By shifting our starting point, we radically alter the possibilities that emerge from it. Shotwell offers a provocative starting point for the decolonization of our imaginations that bears strong similarities to those demonstrated by Graeber & Wengrow in The Dawn of Everything (2021). The authors challenge us to imagine a past in which we have always been compromised or rather been “burned” in spy parlance. What if there was no Garden of Eden; no pure state in which we once lived and in which we might return? What if we have forever been implicated in situations that we at least in some way repudiate? What if the marker of the Anthropocene was not the nuclear age as described in Issue Twenty-Five, but rather a starting point nearly over three hundred years earlier? Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin suggest 1610 as an alternative starting date of the Anthropocene— the lowest point in a decades-long increase in carbon dioxide resulting from the cumulative genocide of over 50 million Indigenous peoples (representing 10% of the total global population). “We are compromised and we have made compromises, and this will continue to be the way we craft the worlds to come, whatever they might turn out to be,” writes Shotwell. “So, what happens if we start from there,” from a point where we recognize our complicity in harm and suffering as our launching-off point for action?

What would surely come as a disappointment to my daughter and many others who hold a vision of a pure past, Shotwell invites us to abandon our imaginary Holocene vision as “a time and state before or without pollution, without impurity, before the fall from innocence, when the world at large is truly beautiful.” This quest for purity colonizes so much of our contemporary imagination, behaviours, and beliefs:

“Living well might feel impossible, and certainly living purely is impossible. The slate has never been clean, and we can’t wipe off the surface to start fresh— there’s no “fresh” to start. Endocrine-disrupting soap doesn’t offer a purity made simple because there isn’t one. All there is, while things perpetually fall apart, is the possibility of acting from where we are. Being against purity means that there is no primordial state we might wish to get back to, no Eden we have desecrated, no pretoxic body we might uncover through enough chia seeds and kombucha. There is not a preracial state we could access, erasing histories of slavery, forced labor on railroads, colonialism, genocide, and their concomitant responsibilities and requirements.”

Shotwell's investigation of purity extends well beyond the more obvious cultural ties to movements such as eugenics into a much more systemic cultural narrative of denial that undergrids much of our consumptive patterns around self-help and personal wellness lifestyles. What is so damaging about this pretense to purity is that it denies our very entanglement with the world as if we can somehow be set apart from it. Shotwell describes purism as “de-collectivizing, de-mobilizing, paradoxical politics.” The pursuit of purity shuts down collective possibilities against the devastation of our world by turning what should be imaginings of responsibility and memory into an obsession with individualism because it seems controllable. “Being continuous with everything on earth is a starting point for critical inquiry, rather than an explanatory end,” writes Shotwell. Instead of seeking to set ourselves apart through personal pursuits of purity or chasing an imagined pure past of true beauty that we are trying to restore, our starting point for productive imaginings is an embrace of the strange, the impure, and the contaminated.

Transitioning from Purity to Plurality

“For every subtle and complicated question, there is a perfectly straightforward answer, which is wrong.” H.L. Mencken (paraphrased)

Mencken’s quote summarizes the dominant cultural conditioning of the Western imagination in moving from the complex to the simple and from the plural to the singular—a practice that many of us are so well-versed in that we don’t even realize we are doing so. In researching The Dawn of Everything, Graeber & Wengrow admit to their initial inquiry question was centred around the rootedness of social inequality in civilization. They quickly realized that such an inquiry was predicated on the preconception of our species falling from some idyllic state of equality, which they knew not to be true, and additionally trapped the possibilities for civilizational reinvention in tight conceptual shackles. What if, as the French anthropologist Pierre Clastres suggests, those so-called simple and innocent ancient people who lived in profoundly different social arrangements were actually more imaginative than we are? As Graeber & Wengrow trample through well-trodden narratives, they find repeated evidence of “compounded simplicity” that results in a kind of cartoon version of history through the simplification of a simplification of a simplification.

The Dawn of Everything is often referred to as mind-blowing because it unravels the conditional present of our social relations as a historic lineage to our past, thus unshackling us from largely homogenous views of our history to recognize the intensive degrees of heterogeneity. Graeber & Wengrow’s description of many pasts dislodges rather than further perpetuates our present, leaving readers left wondering how our past imaginings have been so impoverished for so long.

In his essay “The search for cognitive justice,” Shiv Visvanathan describes this compounded simplicity of cognitive obsolescence as a form of cultural violence, which is precisely what Graeber & Wengrow work so diligently to both establish and avoid in their own narrative. Constructed binaries of backward versus advanced, primitive versus modern, or traditional versus innovative semantically obliviate one in favour of the other. One example is how our entire theory of development relies on linear time as a kind of chronology of past, present, and future, which has in its very conception cultural obsolescence based on what never appears on the timeline. By imagining that our present has a direct and causal link to a singular past, we both relegate the past to history (de-presencing the Indigenous) while also erasing any pasts that fail the linearity test with the present.

To illustrate the point, Visvanathan tells the story of a multiday seminar between 400 weavers and European scholars who gathered in Chirala outside Hyderabad. After a couple of days of seemingly pleasant dialogue in which the weavers sat on the floor and the academics in chairs, a Dutch scholar suggested the scholars too move to the ground. In describing the transformation that occurred, Visvanathan writes:

“From social distance, the seminar moved to a sense of candour between professional and technical equals. As the seminar evolved in this new frame, one of the weavers turned to a historian and said: ‘You have not only destroyed our livelihood, you have taken our theory away from us. You have theorised us out of existence. We need to claim our theory back, to recover our livelihood.’

In this room, a dialogue of difference became the basis of recovery. The documents from Chirala show that the recovery of weaving and the reinvention of colour will be done on the basis of Indigenous chemistry, as natural and synthetic dyes dialogue it out. Indigenous knowledge and theory were recognised as a lifegiving part of livelihood and democracy.”

Visvanathan helps us to conceptualize a society that is located in “multiple time,” whereby we re-present the past through dialogue of difference. This is not about having a tolerance for difference, whereby we create programs for inclusion and diversity. Rather what he is calling for is a much more significant concept of interaction with difference rather than passive acceptance. In a culture of cognitive justice, different knowledges coexist and “our theories to talk to their theories. Our democracy needs a citizenship of knowledge; a dialogue of knowledges.”

The Colombian anthropologist, Arturo Escobar, deepens the cognitive justice theory with the epistemological (knowing) and ontological (being) shifts required to inhabit a world where different knowledges coexist—a world made up of multiple worlds described in Designs for the Pluriverse: Radical Interdependence, Autonomy, and the Making of Worlds (2018). Escobar writes into what he foresees as a necessary civilization transition from the current sociology of absences—when what we can’t imagine is actively made non-existent or non-credible by the current paradigm—to a sociology of emergences that strengthens imagined alternatives to meet the scale and velocity of the defuturing present. This is a radical transition from the Eurocentric, ontological occupation that dictates a specific way of worlding to spaces of social struggle where “we might find more compelling answers to the strong questions posed by the current conjuncture of modern problems with insufficient modern solutions,” writes Escobar.

Recalling Andri Snaer Magnason’s point that new terms and grand concepts are often said but rarely understood because they are untethered from current experiences and emotions, reading pluriverse and multi-world theory can be as easy to gloss over as ocean acidification. Words whose importance dramatically outweigh their contemporary understanding dot our linguistic landscape while their societal impacts continue to compound largely out of cultural sight.

Pluriversality evokes the transition from a colonial single world of capitalist modernity and Englightenment mono-humanism to foster multiple worlds that include myriad forms of relationality and cultural contexts. If we recognize that our planetary existence emerges from our civilizational model of monocultural worlding, it’s imperative that we transition into a global civilization in which many worlds fit as Escobar articulates in “Reframing civilization(s): from critique to transitions.” He offers six-axes for cultural transition which are civilizational corollaries to Elinor Ostrom’s Core Design Principles discussed in Issue Twenty-Six:

Re-communalization of social life

Re-localization of social, economic, and cultural activities

Strengthening of [local] autonomies

De-patriarchalization, decolonization and de-racialization of social relations

Re-integration with the Earth; and

Construction of meshworks among transformative alternatives which creates translation and dissemination between communities

While many/all of these axes can be found as active knowledge systems and ways of being in certain communities who have held strong to Indigenous/traditional systems, homogenous global monoculture has eradicated these axes from most global communities. Escobar suggests that the most important intellectual-political task for cultures transitioning from the dominant Eurocentric neoliberal paradigm begins with “constructing the conditions for such innovative imaginaries.” Otherwise, we risk our institutions and policies failing to deliver viable futures due to the defuturing pressures of their current configurations.

A New Myth of Limits

What if the limitations of our imaginations in approaching systems change exacerbates the underlying conditions of inequality, disempowerment, and separation that sit beneath the headlines and visible manifestations of the system? Are our so-called “green transitions” fraught with the same blindspots and externality-denying capitalism as the systems we seek to replace? As we chase symptoms, is it a failure of imagination that attaches us to the outputs rather than inputs of the systems? Are we so deeply entrenched in the causes that it becomes more desirable to attend to the symptoms for fear of displacing ourselves and our ways of being? Are we struggling with our own cognition in creating the futures that we most desire but perhaps don’t fully comprehend?

Hosseini and Gills argue that our modes of thinking have to be “radically transformed” in order to become “radically transformative.” For most of human history according to the anthropological record, we have relied on mythologies and prophecies as a way of past-presenting imagination. But in a globalized world of capitalist modernity, what are the mythologies we can call upon to guide us to the pluriverse? In Post Growth: Life After Capitalism (2021), Tim Jackson articulates the cultural challenge that undergirds a civilization in transition between myths:

“The role of the cultural myth is to furnish us with a sense of meaning and to provide a sense of continuity in our lives. That need is a perennial one. The loss of a sustaining myth undermines our sense of meaning and threatens our collective wellbeing…A society that allows itself to be steered by a faulty myth risks foundering on the shores of a harsh reality. To cling obstinately to outdated ideas as the world proves them wrong is to court both psychological despair and cultural disaster. But when myths fail, hope itself begins to fade.”

A planet without limits is the outdated myth where we can find our current imagination foundering on the shores. Jackson contrasts our ability to once again hold two contradictory realities: the material limits we’ve come to understand through the modeling of planetary boundaries and the limitlessness of a decolonized imagination. To willingly abandon the dominant mythology of the mantra of more—unmitigated growth through material consumption—we must be able to imagine the greater prosperity of balance that lies on the other side of the transition.

As Jackson realizes, this is a narrative struggle of our own imaginations rather than a quantitative argument of proofs. But in order to overcome the narrative struggle, we must learn to distrust the very patterning functions of current cognition that in part help us to make sense of the world and are simultaneously destroying the planet. In Thinking, Fast and Slow (2013), Daniel Kahneman establishes distinction between System 1 & 2 thinking. Our Systems 1 (fast) patterning does not recognize a planet of limits and that we have for decades been in a state of overshoot, having crossed multiple planetary thresholds (see Bill Rees). We have to repattern our own Systems 2 (slow) mind to resist the illusion by recognizing a certain decision, behaviour, etc. is further exacerbating overshoot. Kahneman explains the Müller-Lyer illusion using the example of two lines that looks to be equal in length according to our Systems 1 mind, but we know they are not in our conscious Systems 2 mind. In order to trust our conscious mind, we must distrust our fast mind. This requires us to recognize the illusory pattern and then recall what our Systems 2 mind tells us to do.

On a Green Transition which Turns Out to be No Transition at All

Rees is confident that our current solutions and resource allocation to climate change mitigation will not reverse global warming and only further worsen our condition of overshoot. The green energy transition is embattled just like any other between those parts of the system that are actively being transitioned with other parts of the system being entirely neglected or being intentionally exacerbated through or past-presencing of approaches. Our consistent failure to think in terms of the systems view of life perpetuates further harm hidden beneath the banner of a new headline. The green transition is accelerating our same failures of the pre-configured imagination, this time recast around a different set of technologies and yet leaving our civilizational transition waiting at the starting gate.

Perhaps the most evocative evidence I’ve found of the costs of our failed imaginings in the green energy transition is James Meek’s brilliant article in The London Review of Books, “Who holds the welding rod?” This long and exhaustive investigative study of CS Wind is not only well worth reading every word, but also a cautionary tale about the defuturing of possibilities based on the continued perpetuation of our globalized capitalist mono-culture into a world factory that takes us from Vietnam to Scotland to Canada to Taiwan to Malaysia following the path of cheapest and least onerous labour. Meek writes,

“The mad dream of a green energy transition might just be starting to come true, with much of the credit due to stubborn activists, clever engineers and a handful of far-sighted policymakers. But it is also happening for the unlikely reason that it has been redefined as a global capitalist consumer project. It realises utopian goals while simultaneously keeping stock markets ticking over, making the rich richer and spreading a general sense of virtue. The systems has been able to turn the green energy transition into a set of products—electric cars, solar panels, wind turbines—but the transition to a world of better treated workers involves systemic changes that are the antithesis of commodification...A world factory demands a world trade union…if we call a global minimum wage—or a global maximum work week, or a global minimum healthcare standard—pie in the sky, we’re saying that the green energy transition is the possible, necessary utopia, and fair pay and conditions the impossible, unnecessary one.”

What Meek discovered, particularly through the investigation of the net-zero ambitions of the UK government, was our imaginations are contaminated in ways far more profound than even those articulated by Alexis Shotwell. We’re trading on human lives as commodities of exchange in equal measure to renewable energy futures. We continue to imagine parts rather than integrated wholes. The outcomes of our decarbonization efforts are interlaced with the societal and planetary damage paralleling other historic responses derived from our failed imaginings.

When I read this quote from Tim Jackson, it hit a resonant chord. It was only through this deep investigation that I now appreciate how central a decolonized, non-pre-configured imagination is as our starting point. That other world out there—the past my daughter dreamt of as beautiful and peaceful and the future the CEO describes in 2050 to accompany their net-zero pledge—is only possible if we prepare our imaginations for civilizational transition. Without that as our starting point, we will continue to impoverish our possible futures by how we imagine them in our present.

“Beyond our material limits...lies another world. A place worth visiting. An investment worth making. A destination worth reaching. Tomorrow is another country. They do things differently there. Beyond the limits to affluence that only limits can reveal to us. Limits are the gateway to the limitless."

Conclusion

This essay explores whether we are capable of imagining a truly different future. By acknowledging that our current planetary crises (climate, poverty, inequality, biodiversity collapse, deforestation) emerge from our dominant civilizational model of Western capitalist modernity, we must simultaneously recognize that we are in a civilizational crisis that requires a transition into a new way of worlding. Our ability to create the conditions for innovative imaginings is perhaps the most important intellectual-political project in fostering a civilization where many knowledges and worlds fit within a single planet.

The challenge is that productive imaginings cannot start from here. Without decolonizing our own imaginations, we will carry forward preconfigured visions of the past into possible futures by replicating and intensifying the present. Our ways of knowing and being have been shaped and curtailed by our dominant worldview, which leads us into a more prescriptive and reductive version of futures than are possible. If our field of view becomes too narrow by design, continuously defutured by knowledges that don’t fit our linear march of historic progress, we will have impoverished our future through the very structure of limited imagination.

Much like a secret agent whose identity has been revealed, we are compromised. By recognizing our historic and contemporary complicity in harm and suffering that has resulted in planetary overshoot, we shift the start point of our imaginations. The transition to the so-called better world begins by changing the way we invite and steward the pluriverse—a world where many knowledges and ways of being exist. Escobar writes:

“Where do we go, then, in this groundless age of loss and wonder (Ogden, 2021), which, paradoxically, takes us closer to Earth, to the sacred, to the spirit, to other forms of the human, that is, to those domains from which modern social theory had largely withdrawn?”

We create the spaces to incubate heterogenous futures where many worlds fit. We start at the point where we are contiguous with everything on earth. We invite the pluriverse that shepherds in an ecologically safe and just space for all life. We transition our imaginings.

Go forth and make a difference in the week ahead.

Adam

If you liked this Issue, please subscribe. The Understory is free and will come to your inbox monthly.

In between issues I share my own reflections and those I have heard from readers. While the term community is often overused and thus abused, The Understory is a community of readers who value the comments of others. Please reply to this email or leave a comment on the website with any reflections you feel comfortable sharing 🙏.

Why I Write The Understory

The goal of The Understory is to inform the decisions of private and public sector leadership while deepening personal connections and commitments to planetary and social health. The hope is to inspire different ways of hearing and seeing opportunities, risks, and challenges, thereby creating a new kind of management publication.

Great change can come from unsettling pursuits. But that possibility can only emerge after taking the time to consider the unsettling and honouring our roles in finding a new path forward. Each issue of The Understory proposes unsettling questions in hopes of helping leadership see a perspective anew or reignite introspection on a concern of personal importance.