I’m pleased you found The Understory—my biweekly essays with critical perspectives on climate change. If you’re here for the first time, hello! Enter your email below to get issues to your inbox, free.

It was a Tuesday, March 7, 1978. Harold N. Weinberg drafted a memo that was at once of both scientific concern and market opportunism. Due to the oil crisis, Exxon had been undertaking bold research projects to consider how they might gradually shift to becoming a diversified energy company. The newly established U.S. Energy Department had just launched a program with nine million dollars in funding to laboratories researching carbon dioxide’s effects. Weinberg’s internal memo was addressed to Executive Vice President, E.J. Gornowski, with “some grandiose thoughts on what we, Exxon, might undertake to do in connection with the ‘CO2 problem’”— to be the initiator of a worldwide research and development effort to understand the effects of CO2 in the atmosphere:

“This may be the kind of opportunity that we are looking for to have Exxon technology, management and leadership resources put into the context of a project aimed at benefitting mankind. What would be more appropriate than for the world’s leading energy company and leading oil company to take the lead in trying to define whether a long-term CO2 problem really exists, and, if so, what counter measures would be appropriate.”

The memo goes on to outline what their leadership role might look like for a “project worthy of Exxon’s talents.” According to InsideClimate News, “Exxon: The Road Not Taken,” over subsequent years executives and employees developed a sophisticated understanding of climate science based on their research initiatives to better understand the effects of rising CO2 concentrations.

On a Friday, four years later, June 18, 1982, Weiberg received a memo that his research budget was going to be reduced by 83% over the next year as “this rate of expenditure should be sufficient to fulfill the Corporation’s needs in the CO2 Greenhouse field.” From 1986 to 1990, in the years where global warming was receiving greatly needed political attention, Weinberg’s budget was reduced to a trickle. In this time period, Exxon did not publish a single peer-reviewed scientific research paper on the CO2 problem (InsideClimate News). In place of scientific clarity, Exxon sharply escalated its efforts to emphasize scientific uncertainty surrounding climate change that would become its position and focus for decades to come. As documented extensively in books such as Losing Earth and Merchants of Doubt, Exxon and its peers sharply amplified messages of scientific uncertainty around climate change through their lobbying, public relations, and advertising efforts which many attribute to stalling the political momentum on action entirely.

By the late 1980s, many corporations and policymakers knew the dire consequences of unabated fossil fuel consumption, as each of us do now. What seems like a story about Exxon is rather a broader metaphor for our ability to take radical turns when we no longer like the path we perceive ahead as the picture becomes clearer. In these moments, we confront the disintegration of an underlying logic that was once foundational to our decisions. When faced with the decision of short-term sacrifices for long-term gain or the status quo, we often embrace distortion and delusion in favour of comfort and desire.

Issue Sixteen is about the myriad distortions that orient us toward two different reality narratives simultaneously: Business as Usual and the Great Unraveling (Macy & Johnstone). These two stories comingle into our ability to carry on with the status quo with a heightened awareness of the fleeting ability to do so. Whether self-imposed or created for our delusion, the ability to sense our current climate reality continues to challenge our sense of urgency in the movement.

A particular set of circumstances have dictated our climate future and determined our distorted present. We’ll return to the middle of the twentieth century to look at when we took a critical turn towards distortion, the obstacles placed in the path of broad climate action in the latter half of the century, and how we can embrace the Great Turning as a new story that returns us to a whole picture of reality. What may at once seem like a path of no return, just as there was a radical deviation towards illusion, there can be a similarly radical turn forwards to reality. While the bridge may have been burned behind us, we might find a way to walk through the flames to reopen a path that once seemed closed.

Reality Distortions at Scale

Before we take a step forward, I’d like to take a small step backwards just a few decades earlier to a time when media distortions and how they were interpreted were not taken as the kind of given that they are today. In her history of the Simulmatics Corporation, If Then, Jill Lepore revisits the early days of computing in the aftermath of World War II. It was a time of transition not just in media from radio to television and computing, but also in the emergence of behavioural science from military to civilian. Through the presidential election campaigns of the 1950s and 1960s in America, Lepore describes how the combination of computation power and behavioural science came to redefine not only how political campaigns would be run thenceforth, but also the emergence of the advertising industry that we know today.

The development of electronic computing machines used to calculate missile trajectories and crack codes during the war led to the development of post-war “giant electronic brain” whose aim was to “replace, as far as possible, the human brain by an electronic digital computer,” in the words of Remington Rand mathematician Murray Hopper. The “electronic brain” that would first come into the public limelight in 1952, UNIVAC, was used to predict the presidential election results on CBS. Given that the computer was eight-tons and the size of a one-car garage, CBS had no space for it in its studios. Instead, they outfitted a teletype machine in the CBS studio that would be connected to UNIVAC in Philadelphia at Remington Rand headquarters. Here is footage from the eve of the election unveiling the processing power of UNIVAC to the American public.

For Lepore, the birth of modern computing represented not just a shift in our computation abilities, but more broadly the corruption of democracy and truth itself. UNIVAC and its offspring shifted our relationship to knowledge. Prediction replaced fact, which Lepore describes as a kind of uncertain knowledge and at the root of many of our contemporary anxieties around fake news, disinformation, and online media more broadly. This nascent prediction engine is the godfather to the algorithms now dictating differing versions of reality depending upon an individual’s preferences. These deceptively clear pictures of reality are in fact illusions that come from computational distortions of knowledge into our own beliefs. Plato’s message in the “Allegory of the Cave” is written on our newsfeeds rather than cast as shadows on the cave wall. The “electronic brain” could now be seen in historic hindsight as a great distortion engine.

By stepping back into the era where this kind of reality distortion was still novel, we are reminded that it doesn’t have to also become acceptable. In what became a year-long series of protests, Lepore recounts the civil rights fever pitch of the Berkeley Free Speech Movement in 1964 that was ignited after volunteers returned from enrolling Mississippi voters as part of Freedom Summer (see Issue Nine). At the time, students at Berkeley and many other universities registered for class using punch cards that were processed on IBM computers. Protestors often wore these punch cards around their necks overwritten with the words “free speech” or “FSM” to demonstrate their opposition to mechanical calculation. Protestors held signs reading “I am a UC student. Please do not bend, fold, spindle, or mutilate me” (Lepore). This sentence was appropriated from the one that could be found printed on most punch cards of the era.

In what became an iconic moment during the Free Speech Movement, one of its leaders, Mario Savio, climbed atop a police car in Sproul Plaza and proclaimed their human plight in the age of the machine:

“There’s a time when the operation of the machine becomes so odious, makes you so sick at heart, that you can’t take part; you can't even tacitly take part, and you've got to put your bodies upon the gears and upon the wheels, upon the levers, upon all the apparatus and you've got to make it stop.”

It is hard to imagine such an earnest appeal at scale today, despite the exponential increase in power and accompanying distortions of our contemporary electronic brains.

Spin Cycles

Just one year before the Berkeley Free Speech Movement and three years after Simulmatics helped John F. Kennedy get elected (The New Yorker, “How the Simulmatics Corporation Invented the Future”), one of the most famous advertising executives, David Ogilvy, published perhaps the most iconic writing in all of advertising literature, Confessions of an Advertising Man (1963). Tucked neatly behind ten chapters on Ogilvy’s insights of how to run a great advertising agency is Chapter XI, “Should Advertising Be Abolished?” It is questionable whether Ogilvy included this chapter at the end so as to close with a conversation around values, or because he considered in all likelihood that most people would not get to the end of the book or may not choose to purchase it with such an opening chapter.

In Chapter XI, Ogilvy recognizes the broad and substantive criticism of the advertising industry, while at the same time gratifyingly stating its approval by the likes of Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill. Ogilvy sought to differentiate fact-based, informative advertising from “combative,” “persuasive” advertising, believing that the former is of a higher order and the type he actively creates:

“If all advertisers would give up flatulent puffery, and turn to the kind of factual, informative advertising which I have provided for Rolls-Royce, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, and Shell, they would not only increase their sales, but they would also place themselves of the side of angels.”

Unlike some other advertising executives, Ogilvy considered himself on the side of angels. And “all serious economists, of whatever political color” also supposedly supported his style of “useful” advertising that provided information. After validating his thinking with social proof, the chapter then changes to a series of questions of which Ogilvy confidently answers. When answering the question should advertising be used in politics, Ogilvy says “I think not...the use of advertising to sell statesmen is the ultimate vulgarity.” Adlai Stevenson and perhaps even Jill Lepore would applaud his position. In pondering whether advertising should be used in “good causes” of a nonpolitical nature, Ogily unabashedly brags of all his firm’s good works on behalf of worthy causes.

Re-reading Ogilvy’s writing in the context of Lepore’s If Then and Bill McKibben’s article in The New Yorker, “When ‘Creatives’ Turn Destructive: Image-Makers and the Climate Crisis (November 21, 2020),” left me wondering whether his distinction between informative and persuasive advertising was in fact overly simplistic. Lepore and McKibben both make the case that being on the right side of advertising history is not always easy, and certainly not entirely evident in one’s own time. McKibben discusses the decades of advertising created for fossil fuel companies before we knew the harmful effects of burning carbon. Lepore describes the hearts and minds style research being conducted in Vietnam to try and influence the outcome of the war. Those involved in these campaigns, up to a certain time, might have considered that they were providing informative, fact-based advertising. Ogilvy even listed his work for Shell in the quote above as a door opener to the heavens.

What Ogilvy lived long enough to see was how, according to researchers Brule, Aronczyk, and Carmichael, the promulgation of informative advertising was being used to sow doubt about climate science (Corporate promotion and climate change: an analysis of key variables affecting advertising spending by major oil corporations, 1986–2015). The researchers found that between 1986-2015, the five major fossil fuel companies (ExxonMobil, Shell, ChevronTexaco, British Petroleum, ConocoPhillips) spent nearly $3.6 billion in advertising purchases for corporate promotion, with the bulk of the spending after 2006. The researchers found that in years where there was more media coverage and congressional action on climate change, a corresponding increase occurred in promotional spending. In their words, “nothing motivates corporate spending on corporate promotion more than media coverage on climate change and congressional action on climate change.” I think even Ogilvy would agree that while masquerading as fact-based, informative advertising, the goal was factual distortion and illusion.

McKibben analyzes how various advertising and public relations efforts have slowed the pace of change around climate action. What he found is that most of the contemporary PR campaigns don’t involve climate denial, but rather factual misinformation such as the significance of algae as a biofuel. Perhaps with David Ogilvy in mind, McKibben shares:

“You could no more persuade a Madison Avenue agency to argue that carbon dioxide is harmless than you could persuade it to argue that Black lives don’t matter. Instead, these campaigns often look for ways to leverage people’s environmental concern in service of precisely the companies that are causing the trouble.”

McKibben further unfolds the internal conflicts happening within ad agencies about supporting this kind of work. Unlike other consulting industries that can assist in the transformation of fossil fuel companies looking to change, advertising and PR companies are in a challenging position to work with fossil fuel companies in a way that doesn’t further their current business, while at the same time remaining compliant with their professional association standards. McKibben found:

The statement of ethics of the American Marketing Association instructs, “Do no harm. This means consciously avoiding harmful actions or omissions by embodying high ethical standards.”

According to the Public Relations Society of America’s code of ethics, “We adhere to the highest standards of accuracy and truth in advancing the interests of those we represent and in communicating with the public.”

The standards of practice of the American Association of Advertising Agencies states, “We will not knowingly create advertising that contains . . . false or misleading statements or exaggerations, visual or verbal.”

Emerging is a cohort of agencies responding to the urging of Extinction Rebellion to disclose climate conflicts in their commitment to Creative Climate Disclosure and to be CleanCreatives and Climate Designers. If your company works with one or more agencies, you can check them against this list and encourage them to become signatories here. It’s worth noting that industries taking a stand on climate action are not limited to advertising and public relations. A similar movement is underfoot in the legal profession. To see the climate scorecard created by the Law Students for Climate Accountability, click here.

Seeing the Whole

In our era where the “giant electronic brain” is hard at work behind the scenes of so many aspects of our lives, how might we overcome signal distortions to sense the possibilities for positive change ahead?

Australian ecologist Val Plumwood maintains that our dominant forms of modern reason, whether economic, political, scientific, or ethical are failing us. Each is subject to their own systemic pattern of distortion and illusion because they are blind to ecological value. It is only when we have models that embrace ecological value for its own sake, and how the natural world provides a life-supporting system to everything on earth, that we might remove some of our current societal distortions.

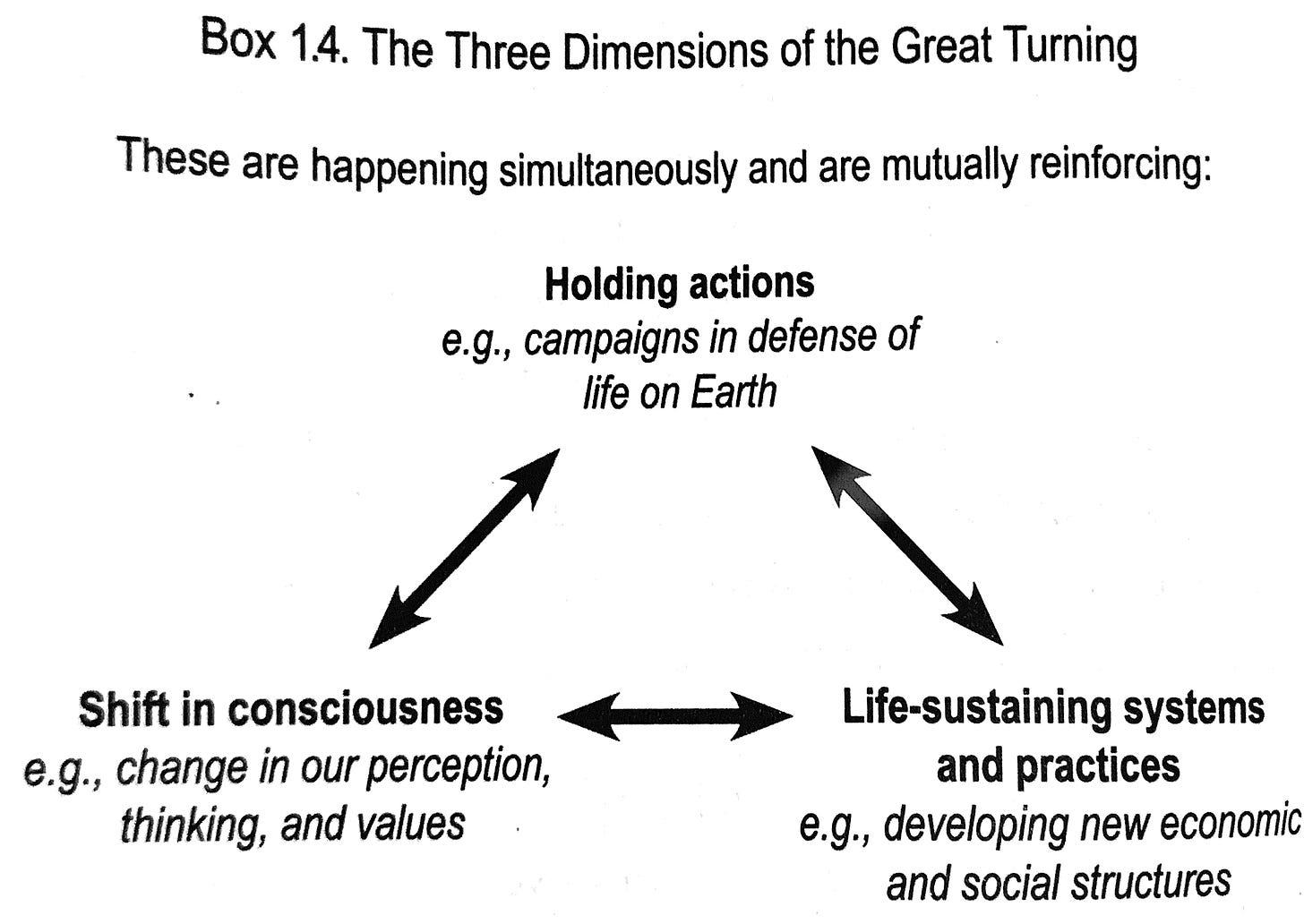

As Joanna Macy and Chris Johnstone write in Active Hope (2012), our new story of the Great Turning tells “what’s catching on is commitment to act for the sake of life on Earth as well as the vision, courage, and solidarity to do so.” Macy and Johnstone suggest that we are unlikely to read about this epic transition in major newspapers or the mainstream media for the reason that they are trained on sudden, discrete events. In other words, they offer their own form of distortions to the larger pattern of change. However, I would contend that since their book was written, myriad alternative media sources have arisen whose attention is fully focused on the Great Turning. We can turn our attention to these alternative sources while training ourselves to recognize the Great Turning taking place based on three dimensions:

Holding actions to stop climate damage

Life-sustaining systems and practices that redesign our approaches to societal structures and systems

Shift in consciousness by strengthening our compassion and cultivating our sense of belonging to the world

In his lifetime, Buckminster Fuller was notorious for creating representations that enable humans to sense ourselves in relationship to the world around us. A concept vital to Fuller’s thinking was “pattern integrities” operating throughout Universe, only a small percentage of which make themselves readily known to humans. One of the most frequent ways Fuller explained pattern integrity is through this idea of a knot:

The knot is a pattern integrity. The rope enables us to physically detect and observe it because it interferes with the rope. Fuller also believed that human beings were pattern integrities and used this way to help explain it. Imagine your day played back as a movie in reverse. But the movie is not just you in reverse, but all of the things that are part of your journey. So the food that you ate at breakfast would be played back to the very farms where it originated. He even suggested journeying backwards with the components of your breakfast to the elemental forms that brought them into being such as the rainwater, solar radiation, and minerals necessary for plant growth. By imagining this backward flow, we can begin to sense the pattern integrities and build an integrated consciousness and vision for how we might redesign our systems according to what can be found in Universe. I am grateful to Lloyd Steven Sieden for his biography, Buckminster Fuller Universe, which has been an enduring resourcing for unpacking Fuller’s complex and in some cases, undecipherable concepts.

While there are many other models and practices for sensing our whole reality to displace distortions and illusions, many colleagues have found great resonance in the ideas expressed by Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski, and Flowers in Presence: An Exploration of Profound Change in People, Organizations, and Society. Their ways of sensing the whole reflects Fuller’s in the dissolution of the boundaries between seer and seen. By redirecting our attention toward the source—as Fuller does to the plant from his breakfast—not only do we find a capacity for empathy through a deepened connection, but also a sense of change and our role in creating it. This comes from our willingness to stop ourselves for moments of “profound disorientation” when we no longer take for granted ways of seeing and making sense of the world. However, it is not suspension alone that will bring about our ability to see from the whole, but rather the redirection of “our awareness toward the generative process that lies behind what we see.” For the authors, presencing goes beyond being fully conscious and aware. Presence is “deep listening, of being open beyond one’s preconceptions and historical ways of making sense.”

Conclusion

It is ironic that the term that has come to be identified with advertising and PR, "spin," is the same term we use to describe the way the earth turns on its axis. The earth’s spin is an entirely vital rotation, whose stationary state would augment the 24 hour day and our entire way of being. Modern advertising and PR spin rarely seems integral to our well-being (and in many cases a violation of it), and whose stationary state would likely result in a clearer picture of reality.

Advertising, public relations, and lobbying are responsible for a significant amount of our system distortions and particularly culpable for our slow progress on climate change. However, these forms became weaponized in the latter part of the twentieth century and even more so in the twenty-first century as the questions of truth and reality have been generated by computational algorithms. When David Ogilvy concluded his Confessions with the quote, “No my darling sister, advertising should not be abolished. But it must be reformed,” I don’t think he comprehended the scale of reform needed. We do not have the factual, informative advertising industry that he celebrated, but rather an industry based on customized persuasions that distance communities from each other and our actual needs and desires for a healthier planet.

Reflecting on the era of human manipulation that she now found herself in, Sylvia Plath is noted for having said to her mother in 1960, “I am skeptical of people whose God is testing.” And we should be too. Through the models of Macy and Johnstone, Fuller, and Senge, Scharmer, Jaworski, and Flowers we can cultivate our own abilities to block out distortions and sense positive possibilities for a different climate future. Henri Bortfot explains that in nature "the part is a place for the presencing of the whole." In Presencing, the authors say that it is this holistic awareness that has been stolen from us if we accept the machine worldview of wholes assembled from replaceable parts. Mario Savio’s statement about the operation of the machine seems even more apt today than it did in 1964: “you’ve got to make it stop.” If we give ourselves permission to suspend our habitual ways of seeing, to be in moments of “profound disorientation,” we can discover the clearer picture of reality on the other side.

Go forth and make a difference in the week ahead.

Adam

In between issues I share my own reflections and those I have heard from readers. While the term community is often overused and thus abused, The Understory is a community of readers who value the comments of others. Please reply to this email or leave a comment on the website with any reflections you feel comfortable sharing 🙏.

If you liked this issue, please subscribe. The Understory is free and will come to your inbox weekly.

Why I Write The Understory

We have crossed the climate-change threshold from emerging to urgent, which demands a transformative response. The scale of the issue demands not only continuous focus but also the courage to take bold action. I've found that a persistence of climate consciousness improves resilience to the noise and distractions of daily life in service of a bigger (and most of the time invisible) long-term cause.

The Understory is my way of organizing the natural and human-made curiosities that capture my attention. Within the words, research, and actions of others lies the inspiration for personal and organizational journeys. I hope that my work here will help to inform not just my persistent consciousness, but yours as well.

I find it infuriating that for decades there have been people who have know what is the right thing to do and it gets stiffled or subverted by the quest for money. Thus reinforcing my mantra that “Being right isn’t enough.” We need to leverage tools used for evil for good. We can just as easily use the tools of advertising and PR for the right side of the issue. Although one needs money or innovative resources by which to do this.

I heard a CBC interview with a botanist who mentioned she apologized to a recent PhD grad that after 40 years in the field she thought we would have been much farther forward on a known and proven issue. Instead of the student being down she told her prof that there was no better time to bring this fixed and working on this issue. I paraphrase but... at a time when we are on a precipice, there is no better time to know where you stand and to make an impact by showing others where to stand on the teeter totter. I just loved that optimistic view. And for us all to keep fighting.

Another thought I had related to reading Homo Sapiens. I have no doubt you have read it Adam, as you seem to have read everything. It really drove home to me the positive and negative in every new scientific step we take. If only we examined these polar positions and the continuum of discoveries in advance of using them or releasing them to “the wild” perhaps we could stop or at the very least be more away of nefarious uses and applications. AI is a good example. Hopefully the horse hasn’t left the barn in that case but even if it has, we have the capability to corral the horses.

Lastly, I need some guidance on your Sylvia Plath quote near the end. I don’t think I connected the dots on that.

LOVE these. Great work Adam.

Note: I apologize in advance for the extensive metaphors; creative flow took over but as always, I'm thankful to Adam for asking us to think deeper.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________

When I imagine great illusions, I think of stage magicians who practices tirelessly to perfect sleight of hand and graduate to levitation, disappearance and telepathy. Honed through repetition, their craft exploits an understanding that humans’ focus is relatively easily distracted such that illusion seems real and in our collective desire for wonder, we willingly surrender our full faculties. This is not to say we might not remain curious or doubtful but the idea that magic exists in a world of process and progress answers a deep hunger for a life that still holds mystery, unexplored frontiers and mystical energies.

Like the Magician, the stage craft of advertising has worked hard, practiced and perfected in an attempt to create a show for which the audience will pay. We are the paying audience; even those among us who attempt to see past the magicians tricks have paid for their seat and the opportunity to argue the distortion.

Our daily lives in the western world are a constant barrage of modern magic. We marvel at the relative ease with which we enjoy comfortable existence. Running water, electricity, a telephone - back a few hundred years and these would all have seemed magical. Today’s conveniences of online shopping, personalized feeds, steaming content and handheld AI are yesterday’s science fiction but they still exist on a backbone of illusion. These presuppose our willingness to appreciate the magic without asking to see behind the magicians apparatus. We are still the audience, paying others for awe and wonder.

In this issue, Adam tackles what is perhaps the greatest challenge to climate action; the nefarious efforts of advertising (corporate narratives) to conjure illusions on behalf of clients motivated by the accumulation of wealth and power. The challenge is that so many of the illusions, or disillusions of climate change seem both obvious tricks but incredibly complex in their unraveling.

When the temporal nature of the show become the persuasive reality of our daily lives, the magic is normalized and we accept it as fact. The omnipotent reach of tech, personalized media feeds and data driven marketing (that knows us better than ourselves) makes us an audience for whom the real illusion is our belief in self-determined choice. We might now ask if the auditorium is growing; can we even opt out of the show?

Is there a different theatre? If we feel that the magician is lacking and instead we attend the theatres of climate awareness and ecological embrace - are we able to break free of capitalism’s spell? I’m challenged by the fact that even the most ardent climate change realists exist in a world where they communicate through mass media’s channels, fund themselves through elite philanthropy, decry the idolization of greed and ambition but ultimately, too often fail to escape the system they rail against. We crumble to convenience, cost savings, entertainment, comfort and conformity. We become theatre within theatre where the magician simply uses the alternative realities as part of his illusion. Think of Green washing, toothless sustainability initiatives, recycling, corporate social impact statements, political posturing and triple bottom line accounting. They all assume that we are capable of simply modifying the show to make it palatable, to extend the run. No longer filled with wonder, I’m convinced I am more aware of the illusions being presented but I’m still in the audience.

I’m not sure how to leave the theatre but I’m more and more convinced that we have to stop watching, to stop providing an audience and run. As I inch for the door, I fear being left with only a ticket stub and fleeting memories. But I fear that as theatre falls around us, the show will go on.