Patagonia’s CEO, Rose Marcario, had a decision to make. Europe has become the centre of the COVID–19 pandemic and all indicators were pointing to the U.S. being hit hard and soon. So on March 13th Patagonia became the first retailer to announce that they would temporarily shut down all operations. All stores would be closed, as would its e-commerce business, offices, and fulfillment centres. Marcario’s letter made clear that the goal above all others was to protect Patagonia’s employees and customers.

While many other retailers floundered in the timing and scale of their response to the pandemic, Patagonia’s action was bold, decisive, and swift. Why was Patagonia first, and what gave them the courage to take such drastic action despite the financial implications?

The decision Marcario was sitting with was made easier by precedents and values established in the company decades ago. In his book Let My People Go Surfing, Patagonia’s founder Yvon Chouinard recounts the impact of the 1991 recession and their painful “Black Wednesday” decision to lay off 120 employees (20% of their workforce at the time). Chouinard’s assessment of the inescapable outcome was “our own company had exceeded its resources and limitations; we had become dependent, like the world economy, on growth we could not sustain.”

After the layoffs, Chouinard decided to whisk twelve of the company’s top managers off to Argentina, back to the namesake region, for a “walkabout.” On returning the company assembled its first Board of Directors. At one of the board meetings where they were struggling with language that summarized their values and mission, board member and ecologist Jerry Mander skipped lunch and crafted a bold document, Our Values.

This ethos would guide the operating decisions of the company going forward, balancing care for the environment with responsibilities to their communities. One statement addressed the hierarchical importance of growth head-on: “Without giving its achievement primacy, we seek to profit on our activities. However, growth and expansion are values not basic to this corporation.” Growth and expansion at Patagonia would henceforth be secondary to social returns.

Issue Two of The Understory explores assumptions about growth. It identifies alternative paths for our personal and organizational development that might just help us avert climate catastrophe, and at the same time provide a higher sense of intrinsic rewards from our work.

The GOD Imperative

What do you feel when you read these words: contraction, downturn, closure, retreat, freeze, slump, slowdown? Now consider these words: overworked, frazzled, fragmented, distracted, overwhelmed, stretched thin. Has the general malaise set in yet? We have been taught that growth and forward momentum of our organizations is positive and essential to survival, while obstacles that slow-down or halt that growth are negative–even at the expense of human and planetary well-being. But must it be so?

When John D. Rockefeller was asked by a reporter how much money is enough, he replied, "just a little bit more." For many of us, the GOD imperative (grow or die) has become so ingrained in our psyche that we remain subconsciously motivated by the ethos, even when it comes into direct conflict with our morality. As a result of COVID-19, many corporations, governments, institutional investors, and central banks have been shaken to their core. With an uncertain future ahead, the question for nearly all remains not whether to rebuild, but how to rebuild. For some with business models in tatters, the next task is to pivot to entirely new business models. Others will try to reignite the engines of growth to make up for deep deficits, and continue the forward momentum shareholders expect.

This is our Black Wednesday moment. It is a momentary shock to the status quo. Many corporate leaders suffering economic impacts from the pandemic likely consider their fate unfortunate. They see a slump in a continually climbing upward curve. But looking at this moment from a different angle, the shock can also be seen as a most fortuitous moment to make a change that has been long required and delayed.

I hope that corporate and public sector leaders take this moment to question their long-held assumptions about continuous growth and the damaging trade-offs required to achieve it. The contraction is a reckoning moment in a path of unsustainable growth for many. And while that means the loss of jobs for some and shareholder value for others, it provides the opportunity for a realignment to an actual, possible future rather than the fictitious, unsurvivable one without growth limits. Should we find the courage to consider an alternate future reality to the one we’ve been trained to imagine, we might just find greater rewards on the other side.

Growth Calculus

In The Ecology of Commerce Paul Hawken simplified the operations of a business down to three variables: “what it takes, what it makes, and what it wastes.” For reasons of brevity, let’s consider a hypothetical business that neither requires external capital to fund current operations, nor its near term expansion plans. A business would typically look at its accumulated capital and seek the highest financial returns. Current business lines would continue to be funded assuming they met the organization’s hurdle rate (minimum rate of return). And any future growth plans would be evaluated from the context of the free cash flow generated in excess of the capital spent to fund the growth with the applied discount rate.

While overly simplistic (I can see my corporate finance professor shaking his head), the profitability of projects is often the dominant (if not the only) driver for making capital allocation decisions. However, we should not stop at this incomplete calculus of growth. Analysis that only considers the financial capital to the exclusion of our natural and human capital is ill-suited to the well-being of humankind and the planet. “Wasting the environment to achieve economic growth is neither economic nor growth,” says Hawken. If our analysis does not include what we take and what we waste, we only have one-third of the growth equation. And if our business ledgers do not account for the true costs of our growth through altered landscapes, ecosystems, and societies, those costs will appear on a ledger somewhere else. The costs exist whether the business accounts for them or not. The question is whose responsibility will it be to pay?

“While living systems are the source of such desired materials as wood, fish, or food, of utmost importance are the services that they offer, services that are far more critical to human prosperity than are renewable resources. A forest provides not only the resource of wood but also the services of water storage and flood management. A healthy environment automatically supplies not only clean air and water, rainfall, ocean productivity, fertile soil, and watershed resilience but also less-appreciated functions as waste processing (both natural and industrial), buffering against the extremes of weather, and regeneration of the atmosphere.”

Paul Hawken, Natural Capitalism

We have built our industrial economy on resource extraction, processing, and manufacturing with little consideration for the ongoing services those resources provide to our commons and well-being when left unaltered. And we continue to pollute our environment downstream with open rather than closed-loop systems that treat the majority of our manufactured discards (plastic, wood, metal, textile) as waste rather than future inputs. As we diminish the planet’s capacity to provide the kinds of services Hawken describes through what we take, make, and waste, we will have to replace these naturally provided services with artificial systems at great costs and upheaval.

Finding Balance

“The skull quadruples in size in the first few years, and if the bones knit together too soon, they restrict the growth of the brain; and if they don’t knit at all the brain remains unprotected. Open enough to grow and closed enough to hold together is what a life must also be. We collage ourselves into being, finding the pieces of a worldview and people to love and reasons to live and then integrate them into a whole, a life consistent with its beliefs and desires, at least if we’re lucky.”

Rebecca Solnit, Reflections on My Nonexistence

As Rebecca Solnit beautifully illustrates, growth is a balancing act. Growth at a measured rate and in service of something with greater primacy than ever-increasing financial returns should be our aspiration. Instead of assuming resources are unlimited (or perhaps cheaper than regenerated ones) what if we challenged our organizations to thrive while minimizing the external inputs to our systems?

In his seminal work Principles of Political Economy (1848), John Stuart Mill conceived of a moment in which a society would have achieved a sufficiently high level of wealth accumulation to temper its growth ambitions. Mill called this the ‘stationary state’—a kind of economic system held in a near-perfect equilibrium:

“It must always have been seen, more or less distinctly, by political economists, that the increase of wealth is not boundless: that at the end of what they term the progressive state lies the stationary state, that all progress in wealth is but a postponement of this, and that each step in advance is an approach to it…I cannot, therefore, regard the stationary state of capital and wealth with the unaffected aversion so generally manifested towards it by political economists of the old school. I am inclined to believe that it would be, on the whole, a very considerable improvement on our present condition...But the best state for human nature is that in which, while no one is poor, no one desires to be richer, nor has any reason to fear being thrust back by the efforts of others to push themselves forward...It is scarcely necessary to remark that a stationary condition of capital and population implies no stationary state of human improvement.”

Mill decoupled human improvement from quantitative growth, recognizing that there would come a time where accumulating further capital would no longer be required. Note that Mill deployed an economically repellant term, “stationary,” to create a positive association where financial capital had fulfilled its aspirations. John Maynard Keynes also greatly anticipated that moment when a society would focus on its ends such as happiness and well-being rather than on the means of economic growth and individual profits. The question then becomes one of recognition: how do we know when we have finally achieved the ends we were ostensibly working to achieve—the idea that economic progress would bring social progress or at least widespread improvement in the conditions of life enjoyed by most people? While too lengthy to cover here, I will write about other perspectives on social progress and other indicators of growth (such as GDP) in future issues of The Understory. However, it should be obvious that corporations need not only look at external indicators of well-being. We can also look at internal indicators to identify whether our organizations have achieved their growth aspirations and can begin limiting the external inputs required to sustain that growth. Here’s what that can look like.

Prescribing Limits

Being first sometimes stings. According to The New York Times, sales at Patagonia are down 50% in North America. Executives have taken pay cuts, and Patagonia furloughed 80% of its retail staff for 90 days. When asked by a journalist about the decline, Marcario said:

“Even if Patagonia becomes a smaller company as a result of the pandemic, it will keep working ‘to protect wild places, to vote climate deniers out of office.’ We were one of the first to shut down, we might be closer to the last to reopen fully—I don’t really care. We are doing everything we can to ensure that our employees are taken care of in the best way possible and we’ll make those decisions as we come to them.”

Two months later the resolve and dedication of Patagonia leadership perseveres even in the face of a shrinking company. Patagonia has gone to great lengths to protect their employees–from the redesign of their fulfilment centres to paid leave and health benefits. Sure, Patagonia can take liberties that management of many public companies (and even some private ones) only dream of—high gross profit margins, die-hard brand loyalty, high employee retention, and expanding market segments. But what often gets overlooked is how each of the decisions and the company’s legacy benefiting from them was made deliberately, even at times with financial sacrifice. As prescribed in Our Values they have focused first on quality, sustainability, and environmental and human health, quadrupling in size over the past decade to a billion-dollar company while making some of the least conventional decisions in retail.

Over the past fifteen years, the company has taken actions that would be seen by many as having the potential to cannibalize their own business:

In 2005 Patagonia started sending employees to college campuses and climbing centers to teach its customers how to repair Patagonia goods and has opened 72 Worn Wear repair centres globally to repair customer clothing.

Marciano worked with supplier Primaloft to develop recycled insulation. It not only transformed Patagonia’s products but was adopted by competitors like Helly Hansen, the North Face, Nike, and Adidas.

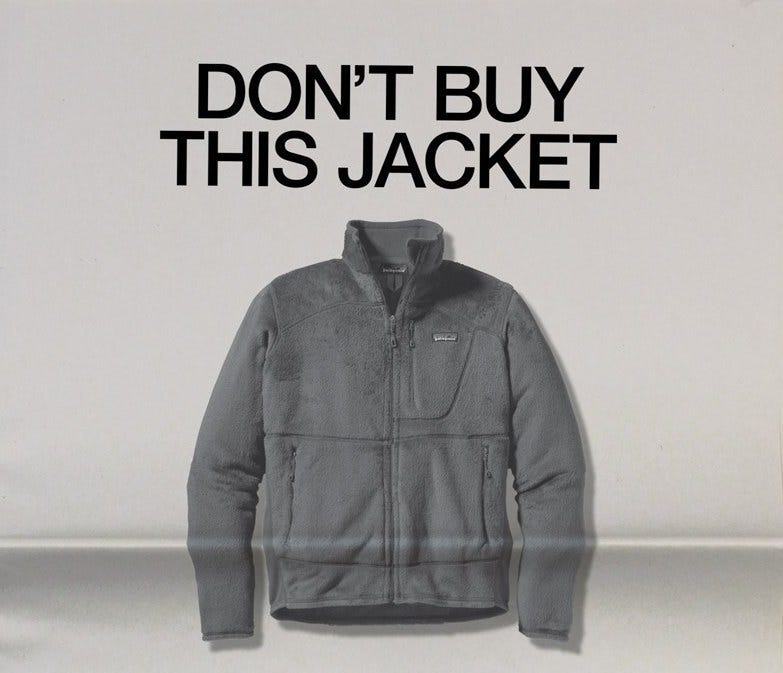

In 2011, Patagonia purchased a full-page Black Friday ad in The New York Times with the headline ‘Don’t Buy This Jacket,’ encouraging customers to repair and reuse as much of their clothing as possible.

In 2013 Patagonia launched the Responsible Economy ad series which disconnected prosperity from economic growth and increased consumption.

Patagonia added Worn Wear to its U.S. website and added a section to each of its retail stores offering customers the chance to buy used Patagonia clothes, and giving trade-in customers gift certificates for future purchases.

The list goes on…

Patagonia long recognized that they were not going to abate or reverse climate change if they didn’t correct the assumptions that were causing it in the first place. This kind of change is difficult, and often goes against the cultural norms of our organizations. However, for many of us, this is precisely the time to be asking the hard questions of our long-held assumptions as we remake our organizations for the future. Imagine this thinking pervading your organization:

“At Patagonia, we start with the knowledge that everything we produce comes at a cost to the environment. We then work continuously to lower the environmental and social costs of our products at every phase of their life cycle—from improving our manufacturing processes at every level of the supply chain to increasing our use of recycled and natural materials to encourage reuse, repair and recycling among our customers.” Our Footprint

By having the courage to recognize that we’ve long exceeded our planetary limits, we can shape a future that requires more from less in our organizations. The path won’t always be easy. By having an explicit set of values that guide current and future decisions like those at Patagonia, it becomes possible to stay the bold course. And in the process of identifying those organizational values, we may just come to realize that the economic moment Mill and Keynes both imagined is already here. We’ve just been having trouble hearing it over the noise from the engines of growth.

Go forth and make a difference in the week ahead.