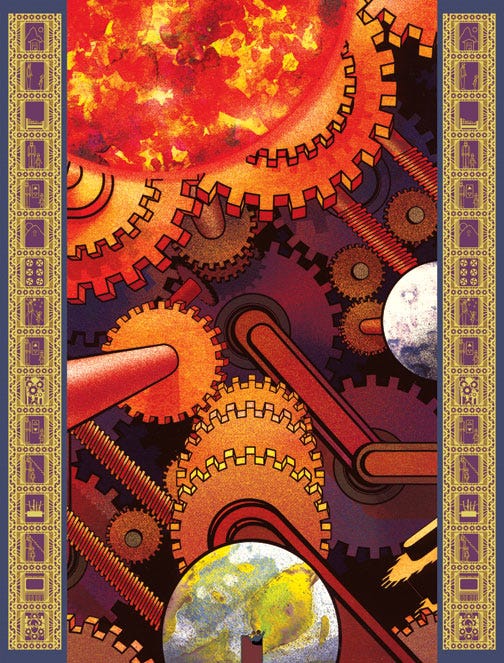

Kevin Tong, The Earth Machine

If you’ve been reading past issues, you may have noticed that I frequently use the term ‘living planet’ to denote Earth. The choice of language is intentional. Perceiving something as living, we are more likely to value its self-organizing properties, as well as its continuous state of adaptation. The language we use to describe our planet’s materials, systems, places, and species affects the way we perceive our place within it, and the choices we make about altering, exploiting, or protecting Earth.

How do you perceive the planet? As an integrated and yet largely unknowable system? As a living thing? Or as a giant, complex machine with interchangeable parts whose outputs can be modified by changing the inputs?

This metaphysical question frames the argument in Climate: A New Story (2018), briefly alluded to in Issue Five. By quantifying the behaviour of the whole planet into its individual parts, Charles Eisenstein believes there is a broader, scientific reductionism at play.

“Its conceit is that someday, when everything has been ordered, classified, and measured, we will have penetrated every mystery and the world will finally be ours. This reduction of reality to quantity is a reduction of the infinite to the finite, the sacred to the mundane, and the qualitative to the quantitative. It is the abnegation of mystery, aspiring to encompass all of reality in its bounds.”

A current example of this quantification of the infinite, the sacred, and the qualitative is the tendency to reduce our environmental challenges to the narrow focus on greenhouse gases. As Eisenstein says, even if we took greenhouse gases to zero, we could continue degrading our ecosystems which will still result in the destruction of Earth by a million different cuts.

In this issue, I consider different conceptual models of the planet, and how those conceptions determine our relationship to it. I’ll turn to the mechanist philosophers–Descartes, Newton, and Leibnitz–to better understand how a particular set of ideas about humans, animals, and nature informs our current sensibility.

A Living Planet Worldview

Eisenstein proposes that the “Story of Separation” explains how many of us live everyday continuing to justify small and large actions in degrading our ecosystems. Before going further, I want to recognize how antithetical this “Story” is to the cosmologies of many indigenous communities and belief systems like Buddhism, to be further explored in future issues. Eisenstein describes the modern sensibility of a “separate self in a world of other.” This ideology (at its roots Eurocentric and imperialist) implies that since I am separate, the very existence of others is a threat to my own well-being. In a world of finite resources, the more someone else gets, the less there is for me and my organization. And if the forces of nature are indifferent to human well-being, I must become their master and control nature to preserve my security. Intelligence, purpose, sentience, agency, and consciousness are presumed to be the domains of humans who can imprint their intelligence on an inanimate world. This “Story of Separation” consequentially:

classifies everything in nature as “environment” and thus distinct from humans;

pictures nature as an incredibly complicated machine (inert, finite, knowable) rather than an adaptable, living system;

values other beings and materials as exploitable resources based on their instrumental utility to humans; and

seeks quantifiable rather than qualitative knowledge.

Eisenstein invites us to transition our thinking from a “geomechanical worldview to a Living Planet worldview.” Harkening back to James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis’s Gaia Theory (1979) that earth functions as a single organism, Eisenstein conceives of the forests, soil, wetlands, coral reefs, seagrass meadows, and mangrove swamps as the planet’s organs, and fish, whales, elephants, and other animals as its tissues.

“A forest is not just a collection of living trees – it is itself alive. The soil is not just a medium in which life grows; the soil is alive. So is a river, a reef, and a sea. Just as it is a lot easier to degrade, to exploit, and to kill a person when one sees the victim as less than human, so too it is easier to kill Earth’s beings when we see them as unliving and unconscious already. The clearcuts, the strip mines, the drained swamps, the oil spills, and so on are inevitable when we see Earth as a dead thing, insensate, an instrumental pile of resources. Our stories are powerful. If we see the world as dead, we will kill it. And if we see the world as alive, we will learn how to serve its healing.”

The aliveness that Eisenstein proposes is a powerful concept for ecological preservation and regeneration when considered alongside its alternatives. Eisenstein wants us to reconnect with our profound love of, empathy, and respect for the natural world. And this story, the one described in the book as “interbeing,” helps us understand how the health of the planet depends on the quality of local ecosystems everywhere; that each of those organs and tissues are vital to a healthy planet.

Before we wrap up this issue with roaring chants for interbeing, I want to dive a bit deeper into some of what Eisenstein is proposing. While not acknowledged directly in his writing, the lineage of questions around animating forces and agency can be traced back several centuries to western philosophers who grappled with (and are partly responsible for) the problems and blindspots of a humanist or human-centred worldview. What prevented Descartes, Newton, and Leibnitz from arriving at a concept of interbeing?

The Architects of Mechanical Earth

Kevin Tong, The Earth Machine

Starting around the mid-seventeenth-century, mechanism became the dominant paradigm of European science. Using the analogy of a clock, the mechanists described the world as a giant machine set in motion by an external force much like a clockmaker winds a spring. Until such external force is exerted, all matter is stable or inert. For the mechanical philosophers, humans were wonderfully complex machines, as were animals and plants. One of the big questions the mechanical philosophers sought to answer was where to locate this external force that animates life. Does it originate within the natural form, in which case nature would be “alive” and self-motivated? Or does the force come from outside, which would then assume a supernatural power?

In The Restless Clock: A History of the Centuries-Long Argument over What Makes Living Things (2016), Jessica Riskin describes this quandary in terms of agency. “A thing with agency is a thing whose activity originates inside itself rather than outside.” Riskin is quick to point out that agency does not assume nor require consciousness. Think of that plant in your house which all of a sudden grows a new shoot. Did it intend to create that shoot? The mechanistic philosophers and most scientists would say absolutely not. Riskin asks:

“Do the order and action in the natural world originate from inside or outside? Either answer raises big problems. Saying ‘inside’ violates the ban on ascriptions of agency to natural phenomena such as cells or molecules, and so risks sounding mystical and magical. Saying ‘outside’ assumes a supernatural source of nature’s order.”

René Descartes, L'homme, et la formation du foetus

For René Descartes, the passive, mechanistic design of nature required the existence of a supernatural force, whether God or a soul animating the body. He left much of that murky in order to avoid the scrutiny and punishment of the church which was a mortal danger for “heretic” predecessors, such as Galileo. Riskin reminds us that “rather than to reduce life to mechanism, he [Descartes] meant to elevate mechanism to explain life, never to explain it away.” Leibniz went further, conceiving of the earth and all plants, animals, and humans as restless internally motivated machines endowed with perception and goal-seeking behaviour. Riskin notes that through philosophy and mathematics, Descartes presumed that humans could unravel the workings of the world and become its masters. While all living things shared the quality of being self-motivated machines, only the clockwork human had the ‘cogito’ (I think therefore I am), which endows humans with the power of rational thought necessary for a will, consciousness, and self-knowledge, also separating the self from other. ‘Cogito’ also endows humans with the ability to know, order, and dominate the animals and plants. Newton later stepped in to provide the scientific tools to expand that knowledge and exercise that control over non-human life on the planet.

The legacy of the mechanical philosophers is the human-centred ordered world that so gravely concerns Eisenstein. A lingering belief that through mathematics a messy and chaotic world could be tamed through explaining and interchanging component parts as needed. A world where a species has a monopoly on reason and a view of the separate self in a world of other. So when Eisenstein laments the “Story of Separation” and the reduction of a living planet to quantity, the finite, and the knowable, he might look for its roots in the mechanistic worldviews articulated by Descartes, Newton, and Leibnitz.

Conclusion

We are continuously learning more about the organs and tissues of our world, and even contradicting those things that we once thought we knew with new evidence. To think that even as recently as the early 1970s we had little to no concept of how plants and trees sense and respond to the environment around them. We are just the inventory of the invisible complexity inherent in each biosphere. Might we some day arrive at the concepts that some animals or plants have agency or even rights? As noted by Steven Shapin in reviewing The Restless Clock, “what counts as agency, intelligence, consciousness and the state of being human is constantly changing in response to cultural and technological realities.” A view of the planet as an infinitely complex and evolving living system enables us to embrace that changing consciousness.

It is all too easy to get caught up in what Eisenstein would call a “tangle of arithmetic”—defaulting to what we know and undervaluing the scale and importance of the unknown in favour of our own cognition, apart from any other. How we choose to perceive the planet is a decision of our own making. We can choose our “felt understanding of the living intelligence and interconnectedness of all things” (Eisenstein) rather than a mechanistic view of the planet as knowable, controllable, and replaceable by humans. As Eisenstein reminds us, the failure to acknowledge our dependence on organs and tissues of the planet as integrated rather than separate from our being is a crisis not just for the earth, but also for humanity. “Love benumbed, we believe that we can inflict damage without suffering damage ourselves.”

So I will go on using the term ‘living planet’ to describe Earth. I hope you will too.

Go forth and make a difference in the week ahead.

Adam

Special thanks to Kevin Tong for granting me permission to share his illustrations. I encourage you to explore more of his work.