Why Walk

Issue Ten: The Understory

“We had a remarkable sunset one day last November. I was walking in a meadow, the source of a small brook, when the sun at last, just before setting, after a cold, gray day, reached a clear stratum in the horizon, and the softest, brightest morning sunlight fell on the dry grass and on the stems of the trees in the opposite horizon and on the leaves of the shrub oaks on the hillside, while our shadows stretched long over the meadow eastward, as if we were the only motes in its beams. It was such a light as we could not have imagined a moment before, and the air also was so warm and serene that nothing was wanting to make a paradise of that meadow. When we reflected that this was not a solitary phenomenon, never to happen again, but that it would happen forever and ever, an infinite number of evenings, and cheer and reassure the latest child that walked there, it was more glorious still."

Henry David Thoreau, Walking

It is nearly the first anniversary of the September 2019 climate strikes when approximately six million people across 150 countries marched for a healthier living planet (The Guardian). As a dedication, I wanted to write an ode to walking in hopes that we hold on to it as seasons change and obstacles challenge our ability to consistently walk. As I write this issue, much of the American West Coast is on fire, making walking outdoors dangerous to impossible for many Understory readers. While these fires are unprecedented in scale and linked directly to climate change, eventually (and let’s hope that is very soon) the fires will subside and regeneration can begin. And while the continued burning of fossil fuels will make more times of year and communities unfit for outdoor habitation, we are reminded just how precious our time is in a world of increasingly fragile ecosystems. By building a regular practice of walking, we express gratitude for the ability to walk across the earth and use it as a way to reconnect with ourselves and the world around us.

Issue Ten proposes that walking may be a radical restorative act to rekindle our love for the people and places around us. Walking can also fight for and preserve the freedoms that we hold dear. In many cases, the choice to walk can be considered an act of resistance—a turning away from a life continuously optimized for efficiency in every moment with prescribed paths determining and limiting our movement. An escape from environments built for cars designed to minimize the interactions and meaning of the journey itself. To walk instead of drive is to choose a purposeful slowness while ensuring we do not further damage the health of the planet. Walking can create a landscape for the mind that would otherwise be consumed by more fragmented attention. We can spend our days cherishing and investing in those between spaces as ones of greater possibility rather than minimizing our unstructured travel time in between places of production.

An Indoor Life

Despite becoming bipedal beings millennia ago, our time spent walking has steadily decreased as we continue to expand our indoor lives. Even before the pandemic Americans and Europeans spent about ninety percent of their time indoors (Allen & Macomber, 2020). As Jill Lepore writes in “Is Staying In Staying Safe?” (The New Yorker, 2020), the time someone spends walking to and from the subway in a given day tallies up to fewer minutes than a whale spends on the surface filling its lungs that same day. According to Rebecca Solnit, we live in a series of disconnected interiors (home, car, office, gym shops). When on foot, walking connects everything—“one lives in the whole world rather than the interiors built up against it.”

The United Nations estimates that the amount of indoor square footage will roughly double worldwide over the next forty years (of course our outdoor spaces will only be diminishing). Lepore skeptically writes how our indoor spaces will become more “healthy” and personalized for our comfort. It will soon take an act of resistance to push against the sedentary tide that will create further justifications for staying indoors rather than outside. While our genetic hardwiring craves a connection to nature, Lepore laments how we try to satisfy that craving with photos of redwoods in hospital waiting rooms or visiting the Grand Canyon on Zoom. In her words, "I used to think these dodges were better than nothing, but I’ve changed my mind. Zoom is usually not better than nothing."

And yet we know that our disconnectedness from nature, the environment, and our communities are challenging the fabric of our civil societies and wreaking havoc on the health of the planet. So with lives increasingly being lived in the private sphere (note I am not including online as the public sphere), how will we rebuild the connections that create more sustainable communities and ecosystems?

Walking Makes Us Human

The practice of walking can heal both our nature and mind-body disconnects given the right conditions and intentions. Walking is not just a way that we interact with people, places, and power spatially, but also how we invest specific meaning into something that is a shared human act.

While there are myriad books written about the history and meaning of walking, Solnit’s Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2001) informed my thinking about the significance of walking in what it means to be human. The classic philosophers of Ancient Greece were known as the Peripatetic School, which translates to “one who walks habitually and extensively.” Jeremy Benthem and John Stuart Mill were known to be obsessive walkers. Thomas Hobbes had a custom walking stick created for him with an inkhorn built into the top so that he could jot down ideas as he walked. Rousseau wrote extensively about walking and appreciated that it enabled him to both be in the world physically, and yet be completely removed from it mentally.

“Walking is a mode of making the world as well as being in it,” says Solnit, which beautifully describes walking as an act of authorship, as well as participating within the public sphere. In The Practice of Everyday Life (2011), Michel de Certeau described this duality as “a walker makes possibilities exist as well as emerge.” Through the act of walking itself, we create footsteps that enunciate space and weave places together according to de Certeau. Imagine this vision the next time you walk—your footsteps creating invisible pathways that draw the shapes of an environment.

The privilege to walk is intricately woven into social-economic histories and power structures. De Certeau and Solnit acknowledge that while our footsteps may seem of our own making, they are more often articulated representations of power. Think of trade routes, sidewalks, malls, trails, maps, and guidebooks—all prescriptive walking systems by design. Our cities are often organized around consumption and production. Nature is often experienced as protected spaces with designed paths for travellers. Whether it was the design of cities, the ownership of private property, forced relocations of tribes and communities, or rules systems that tried to control behaviour in public spaces, where and when we walk has often been dictated or forced upon us rather than chosen. According to Solnit, “a path is a prior interpretation of the best way to traverse a landscape, and to follow a route is to accept an interpretation.”

Is walking inherently a controlled act?

A Right to Roam

Let’s step back into Medieval England. It was a feudal system of “the commons” whereby even though all land was owned and controlled by kings and lords, peasants could live on the land and assume rights in exchange for various types of services. As Ken Illgunas described on the podcast 99% Invisible, in the 15th-century wool prices began rising sharply and landowners were keen for sheep to graze more efficiently. This led to fencing-off pastures, which began a period of enclosure across England with stone walls and hedges demarcating the boundaries of ownership. Entire villages were wiped out, as were the rights of peasants on the commons.

Between 1760-1870 Parliament passed nearly 4,000 acts which resulted in the transfer of one-sixth of England from common lands to enclosed, private property. Most notable of those was the Black Act of 1723, which was created in response to peasants covering their faces in soot and hunting common lands at night. 50 offences were to be punishable by death for those trespassing on private land. And so by the time of the Industrial Revolution in the 19th century, ordinary people were forced to move into the cities out of necessity, as the countryside could no longer support their subsistence. For the first time in English history, a large number of Britons found themselves indoors for most of the day.

It was this combination of land privatization and the rise of the industrial working class that birthed a new movement in England called the right to roam. By the late 1800s working-class Britons had begun creating groups to fight for walking rights. According to Jacobin Magazine, the first northern workers’ rambling club was created in 1900 by George “Bert” Ward. Ward didn’t see rambling merely as escapism from their industrialized life in Sheffield and Manchester but rather tied to a broader socialist ideology of a pathway to human improvement. The dictum of “a rambler made is a man improved” infused the ethos of the movement. This became formalized in organizations like the Manchester Ramblers’ Federation who came to define rambling as a kind of moral and physical “readjustment” to industrial, urban life according to Ben Anderson in “A liberal countryside? The Manchester Ramblers' Federation and the `social readjustment` of urban citizens.”(2011) Ramblers deemed cities “the prisons of economic necessity” and sought freedom in the countryside away from the factories where they toiled and the “plague of smoke”(Dickens) where they lived.

Reportedly visible from the homes and workplaces of Manchester and Sheffield industrial workers, the moors of the Peak District and specifically the area of Kinder Scout became the Sunday destination for approximately 15,000 working-class Mancunians to walk its hills with only the price of a cheap train ticket as admission. The vast majority of Kinder Scout’s reservoirs and mountains were owned by the Duke of Devonshire who wanted to reserve the area for elite grouse shoots (Jacobin). Ramblers were increasingly being verbally and physically abused by gamekeepers on Kinder Scout lands who in part protected the private lands from trespassers.

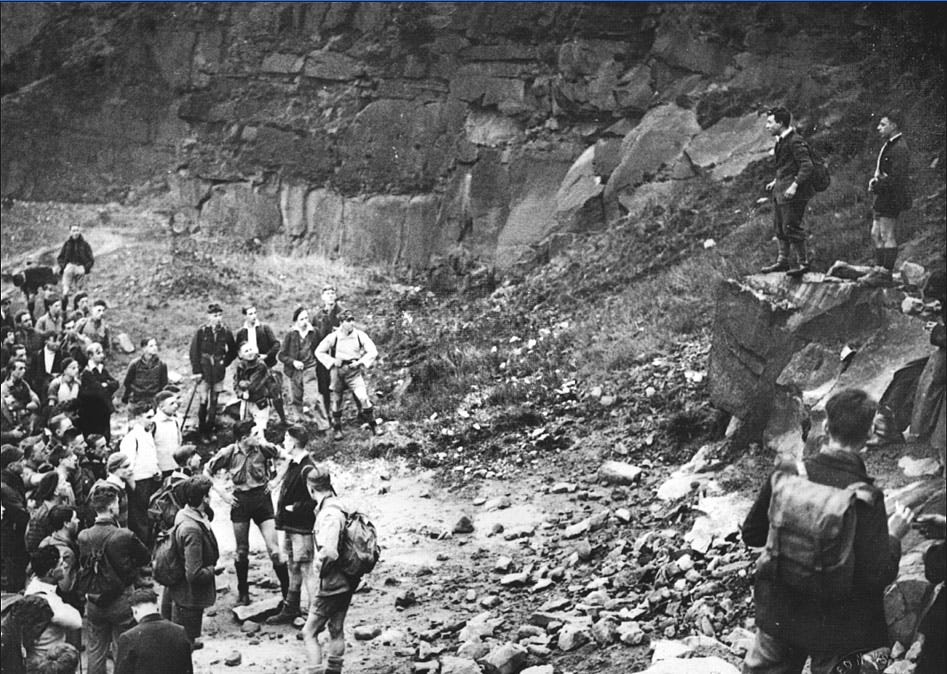

Image Property of Hayfield Kinder Trespass Group

In protest, the British Workers Sports Federation (BWSF) called for ramblers to “take action to open up the fine country at present denied to us” and force working-class leisure onto the political agenda. So in April 1932, the BWSF staged one of the most significant direct labour actions in English history—the Mass Trespass at Kinder Scout. In a coordinated march, over four hundred ramblers overtook the armed gamekeepers in asserting their right to ramble. Five of the marchers were arrested. At their trial, 21-year-old BSWF spokesman Benny Rothman sought an empathetic response to their plight:

“We ramblers, after a hard week’s work, [living] in smoky towns and cities, go out rambling on weekends for relaxation, for a breath of fresh air, and for a little sunshine. And we find, when we go out, that the finest rambling country is closed to us. Because certain individuals wish to shoot for about ten days per annum, we are forced to walk on muddy crowded paths, and denied the pleasure of enjoying, to the utmost, the countryside.”

The grand jury composed of two brigadier generals, three colonels, two majors, three captains, two aldermen, and eleven aristocrats sentenced the men to up to six months in jail on charges of riotous assembly and assault (Jacobin). Three weeks after the Trespass, some 10,000 ramblers gathered at a protest rally. After 17 years of additional protests and direct action, Parliament passed the Access to the Countryside Act, which created Britain's national park system. The first park was in the Peak District.

Nearly 50 years later in 2000, Parliament passed what is perhaps the most striking piece of legislation in terms of the right to roam—The Countryside and Rights of Ways Act. This legislation opened up approximately eight percent of the land in England and 21% of the land in Wales for citizens to roam freely. Norway, Finland, Canada, and Sweden also have partial right to roam legislation protecting the rights of walking with perhaps the most far-reaching being Scotland’s passage in 2003 of the Land Reform Act (more colloquially known as “freedom to roam”) which gives everyone rights of access over land and inland water throughout the country subject to responsible behaviour.

Walking as Freedom

Walking rights versus private property had a long history well before Kinder Scout, and well beyond England. Seventy years before the Mass Trespass, Henry David Thoreau wrote his seminal essay Walking (1862) in Concord, Massachusetts. The increased privatization of land was already evident in Thoreau’s time, and so Walking can be read as his direct assault on attempts to enclose property that would limit the possibilities of walking.

For Thoreau, walking was a source of “absolute freedom and wildness.” He believed that a rich life was one that incorporated the daily practice of walking, as it was inextricably tied to his concept of freedom. To preserve his health and spirits, Thoreau insisted on walking a minimum of four hours a day. Imperative to his health tonic was not just time, but also a state of being that required preparation. While our modern-day preparedness for walks tends to centre around material requirements (fitness gear, cell phone, provisions), Thoreau recognized that the possibilities of a transformative walk were only possible if we freed ourselves from the mental shackles that preoccupy us. Thoreau retorted, “What business have I in the woods, if I am thinking of something out of the woods?”

Even though the essay is entitled Walking, Thoreau preferred the more aspirational term “sauntering.” Taken from religious pilgrims saying they were going “a la sainte terre” (to the Holy Land), Thoreau used “sauntering'' to talk about the societal purpose of walking by an order of people. "He [the walker] is a sort of fourth estate, outside of Church and State and People,” but at once part and parcel of nature. It was this connection with nature rather than society where Thoreau sought out wildness—at the fringes of a society that he intentionally distanced himself from:

“For my part, I feel that with regard to Nature I live a sort of border life, on the confines of a world into which I make occasional and transient forays only, and my patriotism and allegiance to the state into whose territories I seem to retreat are those of a moss-trooper.”

Moss-troopers were outlaws operating between the borders of Scotland and England in the 17th century. For Thoreau, he used them as a metaphor to describe his own borderland between the wildness of nature and the so-called “civilization” of the village. It was in these borders where Thoreau expressed great concern, recognizing that public property might soon be partitioned off as “pleasure grounds, in which a few will take a narrow and exclusive pleasure only.” While Walking was a kind of warning and plea against the further partitioning of private property, I suspect that Thoreau also knew it was an eventuality. Thus, like many outlaws who came before him, he rested comfortably in his outlaw status—sauntering to keep the wildness of nature accessible literally and as a personal Holy Land.

The Walk is the Journey

Thoreau wrote about and dreamt of long journeys. “Every sunset which I witness inspires me with the desire to go to a West as distant and as fair as that into which the sun goes down.” Thoreau believed that journeys westward were where he would discover greater levels of wildness. This historic imagination around the transformative experience of the pilgrims’ journey dates back thousands of years. While many pilgrims today venture by plane with minimal walking, the nature of a walking pilgrimage begins with the first step.

The anthropologists Victor and Edith Turner talk about pilgrimage as a liminal state. As Solnit explains, the word ‘liminal’ comes from the Latin ‘limin’ meaning a threshold. A pilgrim literally and symbolically steps over this threshold when taking their first step, entering “a state of being between one’s past and future identities and thus outside the established order, in a state of possibility.” Entering a liminal state does not require a pilgrimage, but a pilgrimage always involves a liminal state. It is “walking in search of something intangible” (Solnit) that describes the liminal state of being, which Thoreau sought as well.

Solnit identified pilgrimages as one of the most basic modes of walking. There are a few distinctions between a pilgrimage and a typical expedition. The first is that the journey itself is more important than the destination. This is not to say that arriving is not without importance. Solnit describes this as a symbiosis between journey and arrival—"to travel without arriving would be as incomplete as to arrive without having travelled.” The second is that walking is work. Solnit differentiates pilgrimages from secular walks by the level of accommodation made for the walker.

“While secular walking is often accompanied by gear and techniques to make the body comfortable and more efficient, pilgrims, on the other hand, often try to make their journey harder, recalling the origin of the word travel in travail, which also means work, suffering, and the pangs of childbirth.”

While few of us will ever participate in a walking pilgrimage of the scale described above, many of us participate in their contemporary, often secular manifestations—walkathons. In 1970 the March of Dimes held its first walkathon. As Solnit deftly parallels, walkathons “retain much of the content of the pilgrimage: the subject of health and healing, the community of pilgrims, and the earning through suffering or at least exertion.”

The next time you participate in a walkathon know that you too are a pilgrim of sorts, where the journey is more important than the arrival (but you should search out that liminal state elsewhere).

Conclusion

Walking is inextricably tied to what it means to be human and how we create meaning from the world around us. Walking is also one of our most basic forms of motion; however, today it requires an act of deliberate resistance against the forces of optimized efficiency. The 24/7 attention economy minimizes our spaces between places of production, affording little room for embodied engagement in the public sphere.

Benny Rothman, the leader of the Mass Trespass, was fond of saying, “democratic rights are like public footpaths—if you don’t use them, they become hidden, get ploughed up or fenced off, one day to be built over and vanished.” Marching is a way of walking that enables marchers to “make their history rather than suffer it, to measure their strength and test their freedom.” (Solnit)

On this first anniversary of the 2019 climate marches, I encourage you to continue walking as a radical restorative act to reconnect with your community and the planet. The practice of walking can heal both our nature and mind-body disconnects given the right conditions and intentions. While we may not always be able to determine the path, we can choose which journey we take to arrive.

Go forth and walk for a different week ahead.

Adam

In between issues I share my own reflections and those I have heard from readers. While the term community is often overused and thus abused, The Understory is a community of readers who value the comments of others. Please reply to this email or leave a comment on the website with any reflections you feel comfortable sharing 🙏.

I so enjoyed this 'deep dive' into something so basic and 'taken for granted' as walking. Living in rural Colorado, I can perambulate many places ... all on public lands, though. Not so easy in the urban and suburban zones where most of us live. As an outdoor educator, I guide people to a deeper, more conscious connection to Self and Community by 'walking' in Nature.

These are hard times in our country and elsewhere. Let's keep putting one foot in front of the other. Sitting down is good for rest and contemplation, but if we sit too much we may lose some of those footpaths ... and some of our freedoms.

Thank you so much Adam for such a well written piece. I couldn't agree with you more. A friend of mine shared the link to this piece and I just loved reading it. I'll make some time to read the rest too, Understory seems fantastic and very much needed. I'm a huge fan of walking by the way and we do it a lot in the Pyrenees here in Spain. Thank you!