I’m pleased you found The Understory—my biweekly essays on consciousness during the climate emergency. If you’re here for the first time, hello! Enter your email below to get Part Two and subsequent issues in your inbox for free.

This is the first of a two-part issue. To read Part Two, please click here.

Hardly a day goes by without someone in my network remarking how self-interest is at the root of our inability to tackle climate change, biodiversity collapse, ocean acidification, and social inequality. This dread spans across virtually every large collective action problem by injecting a fatalistic mindset that any successful solution requiring cooperation is destined for failure. While this may be the predominant western worldview, it does not have to be the dominant one. What if we can create the conditions for effective cooperation with individuals simultaneously pursuing their self-interest? What if human communities are capable of effectively self-organizing without private and centralized authorities?

Issue Twenty-Six explores alternative structures that create the optimal conditions for endowing people with the desire and responsibilities to cooperatively regenerate a healthier living planet. The questions in this issue emerge from conversations I’ve been having over the past few months about whether we’ve optimized our civic and institutional organizations for planetary health and human well-being. This Issue builds on the framing question from Prosocial: Using Evolutionary Science to Build Productive, Equitable, and Collaborative Groups (2019): “How can we support ourselves in order to act together in such a way that satisfies our own interest, the interests of our groups and the interests of the larger systems of which our group is part?” And the question Kate Raworth used to open her course on Doughnut Economics: “How can our city be a home to thriving people, in a thriving place, whilst respecting the wellbeing of all people, and the health of the whole planet?”

This Issue looks to two progenitors of the commons movement—Elinor Ostrom and Robert Axelrod—who find the notion that humanity is caught in a trap (the tragedy of the commons) or imprisoned (prisoner’s dilemma) both unacceptable and out-of-step with our evolutionary lineage. Through Ostrom and Axelrod we discover new possibility spaces and structures for cooperation that challenge the very efficacy of our institutional arrangements currently tasked with tackling issues of existential importance such as biodiversity loss, ocean acidification, rising atmospheric carbon dioxide, challenged access to clean water, soil erosion, and widening social inequality. We begin to understand how individual behaviour is shaped by the context in which interactions take place, which inspires Ostrom to suggest “we need to develop a better theoretical understanding of human behavior as well as of the impact of the diverse contexts that humans face.”

I chose to divide this Issue into two parts, as it became lengthier than I imagined when first embarking on the research. Part One provides the historic and theoretical context for understanding the commons. Part Two explores the depth of insights and solutions Axelrod and Ostrom propose to find more constructive solutions to how we can govern the commons sustainably and equitably, together.

Trespassing the Commons

Nick Hayes begins The Book of Trespass (2020) returning to the lands surrounding his childhood home between West Berkshire and Oxford to illustrate an upcoming graphic novel. He entitles the opening chapter, Badger, as an ode to the ethos of one of the principal characters of The Wind and the Willows (written nearby), Mr. Badger, who expounds: “Any friend of mine walks where he likes in this country, or I’ll want to know the reason why.” His chapter name also honours the way badgers circumnavigate landscapes with little regard for human-made enclosures.

On a December day, Hayes recounts walking across snowy woods that lead into a valley. From the valley bottom, Hayes finds a path that veers off the Right of Way. This badger track leads him through the woods to and eventually under a wire fence. Being a human, Hayes climbs rather than scuffles below the fence soon to be in full view of a large farmhouse—a sign that perhaps these lands were not as wild as they seem. Over the next year, Hayes returns again and again to this dell, continuing to follow badger tracks “that crossed the woods, cutting through the clouds of bluebells, the forests of ferns and nettles, the clumps of bramble, on the tracks that barrelled through the bracken, bust under fences and burrowed through hedges.”

Hayes recalls a stroll in the countryside with his mother “when the real world caught up with me.” Up to this point, Hayes’ encounters with other living species were beehives, spring flowers, and a kingfisher. However, this day Hayes no longer travels as he once did as a badger. He is a human with the so-called rights and responsibilities that accompany our species. Chugging across the paddock on a quad bike came a human who intercepts their path, declaring “You’ve got no right to be here. You’re trespassing.” Hayes and his mother apologize and leave the land, but the power of these words never settle with him. How is it that just two sentences can reverse the direction of two adults by the will of another? Hayes recalls,

“It was as if his words had cast a spell that had tied our feet and dragged us away...We felt a flush of guilt, a moral sense of being in the wrong, but there was also a sense of being wronged: the abruptness of the intrusion, the absolutism of his approach.”

The spell that Hayes describes is centuries in the making and one that shapes our contemporary worldview so distinctly that few of us even have a felt sense of being wronged. Having rights in land with the ability to own private property entitles the owner with rights to determine who accesses the land, its uses, and well-being. The law and our institutional frameworks privilege ownership of planetary life-support systems with the belief that self-interest entitled by private ownership results in the best stewardship outcomes. Hayes asks us to consider how we arrived at our contemporary moment where the majority of our nations’ lands and waterways are enclosed and cut-off from access, and how that affects the well-being of our human and more than human communities. He challenges us to imagine a country not based on historic division, but rather one of shared history and relationship with the land. Within Hayes’ narrative is an enquiry into how cumulative enclosures and legal changes result in a nation where 92% of its lands are private and 97% of its waterways are inaccessible.

Understanding the Commons

Language both describes and informs cultural worldviews. How has one of the noblest societal ideals, "shared by all," lost its sacredness in modern usage? In the English language, the word "common" has become a derogatory term as we increasingly revere the individual over the collective. To be called “common” would feel to many of us like an insult to our significance, as would someone labelling our artifacts of cultural production and mechanisms by which we produce them “common.” We seek to be “innovative,” “disruptive,” “special,” “award-winning,” “thought-leading,” and the like. However we self describe, I am guessing virtually no one would do so as “common” today.

According to Hayes, the Romans brought with them sacred categories of commons land ownership when they invaded Britain. Four different resources were off-limits to privatization: res communes (air & sea), res publicae (rivers, parks, public roads), res universitas (public baths & theatres), and res nullius (wasteland, cattle pasture, woodland, wild animals). Well after Roman occupying forces left England, open-field systems could be found across the country where peasants collectively farmed with resources shared by those who lived in the community.

The commons took a radical turn under William the Conqueror in the 11th century. He led a campaign of distributing lands to French Barons who were conscripted to monitor the Anglo-Saxons while simultaneously beginning a mass enclosure of the commons to preserve pristine deer hunting grounds. The division between aristocracy and commoners was solidified politically under the reign of Edward III in the 14th century. English Parliament divided into upper and lower houses. Members from each borough joined the House of Commons, while clergy and noblemen joined the House of Lords This distinction between a democratically elected House and one primarily of ancestral lineage persists today. Currently, the aristocracy owns one-third of British lands and benefits disproportionally from the estimated 3.8 billion pounds per year in tax subsidies. George Monbiot describes the contemporary state of the English commons succinctly:

“After being brutally evicted from the land through centuries of enclosure, we have learned not to go there—even in our minds. To engage in this question feels like trespass, though we have handed over so much of our money that we could have bought all the land in Britain several times over.”

Hayes intimately understands how centuries of enclosure change the fabric of British culture and community. He describes that while country paths are the heeled traces of democracy in mud, enclosure barriers such as walls and fences are dictatorial by mentally and physically exercising control”

“If those that own the land can dictate what happens on the land, then this private elite can conduct those in society who have nowhere else to be but the land. Race, class, gender, health, income are all divisions imposed upon society by the power that operates on it; if this power is sourced in property, then the fences that divide England are not just symbols of the partition of people, but the very cause of it.”

This relationship between ownership and authority that so troubles Hayes is deeply explored in the work of Vincent and Elinor Ostrom. As she explains in her Nobel Prize lecture in 2009, Elinor Ostrom takes issue with the nomenclature resource economists use when referring to the commons as “common property resources.” The Ostroms fear that combining the term “property” with “resource” confounds the desire to understand the nature of a good with whether it is owned or not. The Ostroms instead prefer to describe forests, water systems, fisheries, the atmosphere, pastures, etc. as “common-pool resources.” By substituting “pool” for “property,” the Ostroms seek to leave open the question of resource ownership and management.

False Binaries

Many issues of The Understory are studies of false binaries—how our attraction to universal economic and scientific models reduces complex systems into simplistic either/or choices. With the commons, the Ostroms and others seek to expand our concepts of the possible beyond either privatization or management by a central authority. Our creative opportunity is to embrace an understanding of a polyvalent human world that reflects the complexity of thriving and healthy ecosystems. We can ask bigger questions that not only disprove a world of simplistic binary options, but even more importantly open up a host of other emerging possibilities typically outside of mainstream consideration.

Most western cultures have seemingly abandoned examples and metaphors of complexity whereby common-pool resources (CPR) can be effectively managed by groups of individuals. As Elinor Ostrom writes in Governing the Commons (1990), advocates are often divided on the roles of central authorities: one set believes in unitary decision-making, while the other believes they should parcel out ownership rights to private self-interests:

"Both centralization advocates and privatization advocates accept as a central tenet that institutional change must come from outside and be imposed on the individuals affected...Contradictory positions cannot both be right. I do not argue for either of these positions. Rather, I argue that both are too sweeping in their claims. Instead of there being a single solution to a single problem, I argue that many solutions exist to cope with many different problems.”

Breaking apart this false binary of central authorities became the career-long pursuit of Ostrom who looks at the science of “getting the institutions right.” She proves that neither the state nor market are uniformly successful in supporting the long-term, sustainable use of natural resource systems, so why wouldn’t we search for alternatives? After all, communities of individuals have historically demonstrated "reasonable degrees of success over long periods of time” in managing resource systems with institutions that were neither state nor market.

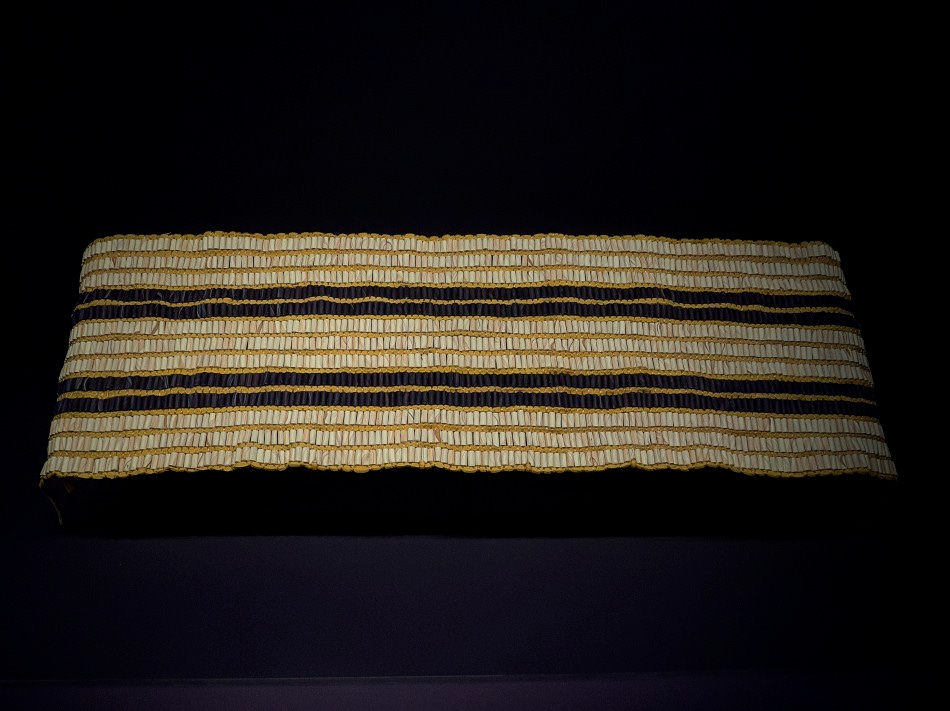

We know that many historic and even contemporary cultures flourish with collective rather than individualistic, self-interested worldviews. In the Reflections on Issue Twenty-Two, I shared Melanie Goodchild’s article on the Two-Row Wampum Belt that symbolizes the 1613 treaty between the Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois) and the Dutch merchants. The two purple rows of beads signal internal pluralism: the Mohawk canoe and the Dutch sailing ship existing side-by-side. Goodchild writes how the rows remain parallel without intersecting which outlines a “dialogical Indigenous-European framework for how healthy relationships between peoples from different ‘laws and beliefs’ can be established.” Ostrom calls these “polycentric” centres of decision-making whereby they function independently while recognizing an interdependent system of relations.

Quoting Daniel Coleman’s paper, Goodchild emphasizes that a both/and relationship of interdependence and independence were vital to cooperative relationships between the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the Dutch: “healthy relationships recognize rather than suppress differences.” Goodchild quotes Dan Longboat on the sacredness of when differences come together:

“Within our context of it as Haudenosaunee, whenever individuals or two things come together to make an agreement, whenever they collaborate, whenever they do that it is two individuals coming together, then the space in between them is the sacred space; you can kind of think about it in terms of how they are respectful towards one another, how they are caring and compassionate towards each other, how they are empathetic with one another.”

This sacred space that emerges from the cooperation between two or more individuals, organizations, or nations is a concept I’d like to carry forward as we first look to the prescriptive outcomes of some of the most iconic economic theories of the 20th-century based on competition and scarcity.

Theories of Self-Interest

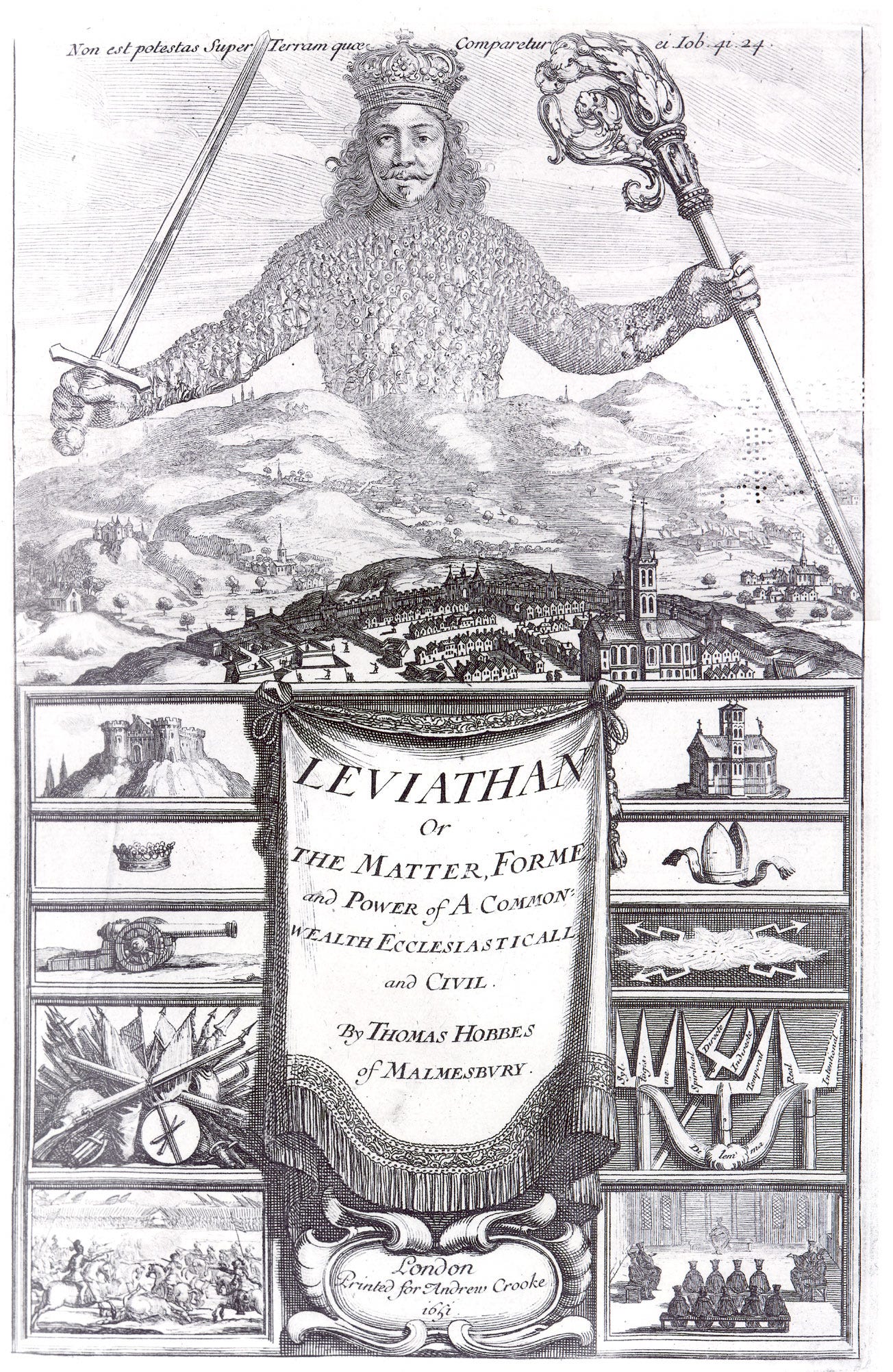

Fear of cooperation descending into anarchy has been deeply lodged in our western hearts by Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan (1651). According to Ostrom and Robert Axelrod in The Evolution of Cooperation (1984), Hobbes’ belief in hierarchical government as necessary to induce compliance from self-interested citizens and officials is at the root of our current natural resource systems of control. The tragedy of the commons, the prisoner's dilemma, and the logic of collective action all have philosophical lineage we can trace back to Hobbes in defining ways that individuals respond when faced with individual versus collective consequences. The tragedy of the commons anticipates overharvesting by the few to the detriment of the many. The prisoner’s dilemma anticipates harming the other player in hopes of higher personal gains. The logic of collective action predicts that groups create the conditions for individuals to “free-ride,” whereby they contribute less because they anticipate others will contribute on their behalf.

These three theories recognize more complex social behaviours than our simplistic games that have single winners and losers. Axelrod found that in these complex systems, under the right conditional arrangements and social behaviours, cooperation could not only result, but also yield more favourable results:

“We are used to thinking about competitions in which there is only one winner, competitions such as football or chess. But the world is rarely like that. In a vast range of situations, mutual cooperation can be better for both sides than mutual defection. The key to doing well lies not in overcoming others, but in eliciting their cooperation.”

Ostrom summarizes the scholarly effort of mid-twentieth century economists and political scientists that originate these three theories as trying “to fit the world into simple models and to criticize institutional arrangements that did not fit.” Perhaps the tragedy of the commons was met with such widespread cultural acceptance because it rationalizes our fears that individuals systematically take more than they reciprocate and thus are destined to delete common pools of resources without a central authority overseer or private ownership. Ostrom says we were willing to accept the prediction of no cooperation because it validates our worldview of scarcity.

According to Axelrod, the tragedy of the commons, the prisoner's dilemma, and the logic of collective action rely upon the assumption of individuals who make decisions rationally based on:

an understanding of all possible strategies,

predictable potential behaviours of others, and

clarity on their own preferences based on which will maximize their expected utility.

Of course we now understand that:

most strategies are often unknown in a complex system,

we cannot possibly anticipate all of the potential likely behaviours of others, and

most people don’t know what they want even well-enough to be rational, self-interested species.

Theoretically, homo economicus is dead (see Issue Eleven), but as Kate Raworth explains, “what had started as a model of man had turned into a model for man.” This is what leads Axelrod to describe the prisoner’s dilemma as the “E. coli of social psychology” given its epidemic level of contagion. Ostrom suggests that hearing the words “tragedy of the commons” triggers the metaphoric eventuality of the degradation of the environment by individuals in collectively managing a scarce resource. We have so internalized these models into our western worldview that even compelling proof that they are wrong by Raworth, Ostrom, Axelrod, and others fails to dislodge them. Ostrom explains the differing context for prisoners from the real-world context on the commons:

“The prisoners in the famous dilemma cannot change the constraints imposed on them by the district attorney; they are in jail. Not all users of natural resources are similarly incapable of changing their constraints. As long as individuals are viewed as prisoners, policy prescriptions will address this metaphor. I would rather address the question of how to enhance the capabilities of those involved to change the constraining rules of the game to lead to outcomes other than remorseless tragedies.”

Part Two of Issue Twenty-Six begins with the question Ostrom proposes—how can we change the constraining rules that lead to productive, sustainable, and even optimal outcomes for the management of our common-pool resources without command from a central authority? I’ll nuance Ostrom’s design principles with those Axelrod proposes to answer his three critical questions of how we escape the prisoner’s dilemma:

“First, how can a potentially cooperative strategy get an initial foothold in an environment which is predominantly noncooperative?

Second, What type of strategy can thrive in a variegated environment composed of other individuals using a wide diversity of more or less sophisticated strategies?

Third, under what conditions can such a strategy, once fully established among a group of people, resist invasion by a less cooperative strategy?”

Conclusion

If we are honest with ourselves, most of us hold a worldview that better cooperation is unlikely to actually lead to better outcomes for us individually or societally. We’ve been indoctrinated into the worldview of self-interest being the engine of progress. We learned the prisoner’s dilemma that we are better off defecting than cooperating in hopes that the other person does the same. We’ve been told that a shared commons results in a tragedy of overexploitation by the few, which harms the many. We’ve learned to anticipate that others will free-ride based on our efforts. This inherited skepticism of the tragedy of the commons, the prisoner's dilemma, and the logic of collective action from the mid-twentieth century results in operating metaphors for how we choose to (or not to) cooperate on complex systems such as climate change, biodiversity collapse, ocean acidification, and social inequality.

Through the work of Elinor Ostrom and Robert Axelrod, we’re beginning to understand that humans have a much more complex motivational structure and more capabilities than rational-choice theory suggests. In fact, the very collective structures Ostrom and Axelrod propose represent the greatest possibility for how we restore feelings and behaviours of responsibility and reciprocity by changing the rules by which we manage our common planet.

Adam

If you liked this Issue, please subscribe. The Understory is free and will come to your inbox weekly.

In between issues I share my own reflections and those I have heard from readers. While the term community is often overused and thus abused, The Understory is a community of readers who value the comments of others. Please reply to this email or leave a comment on the website with any reflections you feel comfortable sharing 🙏.

Why I Write The Understory

We have crossed the climate-change threshold from emerging to urgent, which demands a transformative response. The scale of the issue demands not only continuous focus but also the courage to take bold action. I've found that the persistence of climate consciousness improves resilience to the noise and distractions of daily life in service of a bigger (and most of the time invisible) long-term cause.

The Understory is my way of organizing the natural and human-made curiosities that capture my attention. Within the words, research, and actions of others lies the inspiration for personal and organizational journeys. I hope that my work here will help to inform not just my persistent consciousness, but yours as well.

This is the key question and realization, "What if human communities are capable of effectively self-organizing without private and centralized authorities?" Based on the work of Rebecca Solnit, our world is not 'nature red of tooth and claw' but instead our crises are marked by humans coming to mutual aid and assistance. Chips are down, now, and we will need to neatly sidestep some of the existing (too old, too slow) structures to give room for new leadership styles, new leaders, new structures to come into being.

The intelligence test that we are currently failing is the continued cleaving to the illusion that we are somehow separate from our own biosphere. This is where any approaches to help large numbers of humans reach what Bill Plotkin and others have termed Eco-Awakening becomes important. We need a consciousness shift that will enable us to change our selves at the level of being, and then we will make the right choices and collaborate from that place, that way of being.

Clearly, one aspect of that is what you treat here, and what Tyson Y. has also mentioned, the concept of land ownership is one that no longer serves us as a species, if it ever did serve the species (rather than only serving the oligarchy).

With regards to concepts of competition and scarcity, I'll simply point again at both Thich Nhat Hanh's jewel-like folio, Interbeing (in which he introduced his concept of 'enoughness') and James P. Carse's wonderfly book, Finite and Infinite Games. The planet and the universe provide more than enough for all - what is limiting us is the greed and fear of a relative few. Let us instead play the infinite game together.

China moved back and forth from the highly structured system of Confucianism in times of peace, to the highly fluid philosophy and way of being reflected in Taoism in times of massive disruption (war, famine, natural disasters, etc.). May we learn from that example and not cleave too tightly to our structures when they will not serve us. It is time to swim away from the sinking boat, and those who are stronger swimmers can assist others to bind together what we can to build a new floating community of our disparate parts.

Your quality of research and writing continues to expand - be thinking about how this all may come together as a book?

This is a great read and anticipating Part II. If identifying problem subset(s), informing and counting the many who are interested regardless of nation states, corporate interests might be a goal, some hints are drawn from Dee Hock's Birth of the Chaordic Age.