How Do You Know?

Issue Seven: The Understory

“I can lose my hands and still live. I can lose my legs and still live. I can lose my eyes and still live. . . . But if I lose the air I die. If I lose the sun I die. If I lose the earth I die. If I lose the water I die. If I lose the plants and animals I die. All of these things are more a part of me, more essential to my every breath, than is my so-called body. What is my real body? ... We are not autonomous, self-sufficient beings as European mythology teaches … We are rooted just like the trees. But our roots come out of our nose and mouth, like an umbilical cord, forever connected with the rest of the world.” Jack D. Forbes, Columbus and Other Cannibals

Every day we face myriad decisions—for our organizations, governments, communities, families, and ourselves. Most are of seemingly minor consequences with some that have a different level of significance. Underneath each of those decisions lies a worldview that shapes how we process information, weigh tradeoffs, and rationalize our internal logic. Our rootedness as described by Forbes interconnects or separates us, determining not just how we decide, but also how we feel during and after we make decisions. Many of us go through entire lives without challenging that worldview and our ways of knowing.

The worldview we know is often the only one within our grasp. It is easy to take for granted the knowledge system prescribed to us based on the epistemology of our culture. And in that same stroke of assimilation comes an invisibility and casting off of other ways of knowing. They become invisible to us because they don’t fit our pictures. We choose not to hear because listening becomes its own difficult act of accommodation:

The language is foreign;

The cadence is different;

The assumptions are challenging;

The operating norms are discordant with our own; and

The potential sacrifices are undesirable.

And yet at a fundamental level, many of us would openly acknowledge that we live in a broken system. One where we continuously devalue and denigrate the health of the planet. We willingly privilege the rights, health, prosperity, and education of some over others.

We’ve come to embrace a dispassionate way of living, as it is otherwise difficult to operate within a system that has so many recognizable injustices. If we cannot find the ten minutes in our day to read a full article in one sitting as discussed in Issue Three, how will we find the space to accommodate other ways of knowing? We are challenged to embrace multiple ways of knowing—reconciling the ways we have been conditioned with those of other cultures who have an abundance to teach us.

As University of Michigan psychology professor, Stephanie Fryberg, notes, “modern racism is the active writing of Indian people out of contemporary life.” We cast-off Indigenous ways of knowing as quaint or spiritual because of irreconcilable differences with our late-capitalist lifestyles. Indigenous cosmologies impose uncomfortable limits on things we consider inherent freedoms like wealth accumulation at the expense of deteriorating the wealth of nature.

Dismissing Indigenous ways of knowing is a travesty to our individual relationships with people, plants, animals, land, and water. This Issue seeks to outline how we might live a life that repairs these relationships informed by Indigenous cosmologies. As the language of Indigenous knowledge holders is so important to what is being communicated (even in translated form), I use quotes more frequently in this issue than I have in others, as summaries often seemed inadequate to capture their essence.

Scientific Ways of Knowing

From here forward I will be using the term “Indigenous” to describe Canadian and American “Native” nations and communities. As Jack D. Forbes notes in the article “Indigenous Americans: Spirituality and Ecos,” “many Native nations prefer to use their own language to refer to the group: for example, Diné for Navajo. There is no ideal generic term to apply across nations.”

Perhaps in reading Issue Six you found the “Story of Separation” disheartening. I hope so. Charles Eisenstein articulates why it is important for us to feel interconnected rather than separate. Assuming we’ve recognized how vital and urgent this change in course is to our relationships with the living planet and each other, how to live the change amidst the accelerating demands of our 24/7 world may feel impossible. What is missing from Climate: A New Story (2018) (aside from the publishing requirement of a tidy checklist) are the nuances of moving from why to how we can live with a greater interconnectedness. This issue seeks to provide one of those paths.

As promised last week, I’d likely to briefly revisit the discussion of the mechanistic philosophers of the 17th and 18th centuries. The Cartesian worldview still predominates western, modern thinking–through objective intuition and deduction we can make sense of a chaotic world. The Cartesian duality separated the mind from the body and the observed from the observer. The human body, animals, and plants were part of the physical world, operating like machines according to the unconscious laws of matter. However, the mind existed outside the physical realm with human beings the only dualistic creatures to contain it.

In The Art of Somatic Coaching, Richard Strozzi-Heckler summarizes the significance of this fissure: “this was the beginning of the Western model of mind, body, and spirit existing in separate compartments. We work Monday through Friday; we go to church on Sunday.” This enabled scientists to observe and experiment in order to quantify the mechanisms of nature, without being impeded by spiritual qualities mucking up the works:

“With our educational institutions now firmly grounded in mathematical thinking, instrumental reasoning, and pseudo-scientific approaches, we now equate the human body with a machine and thinking with a computer. We employ reason and logic to determine our relationship with nature, with those we love, teams, and within organizations. We are so firmly entrenched in this way of seeing that we have become blind to it. Social scientists, economists, and world leaders have become indecisive in taking action because of a concern that the pragmatic, heartfelt application, regardless of how successful, won't match established theory.” Richard Strozzi-Heckler

The situation we now find ourselves in with dispassionate leaders and relationships moderated by logic and reason need not be our endpoint, even though the path of how we got here is becoming increasingly clear. Unfortunately that path will not be altered by surface fixes to a broken system with carbon offsets, bans on single-use plastics, and ESG investment portfolios. While all three of those are important, they don’t require challenging our worldview. I am increasingly convinced that a change to our worldview is what is required to alter the fundamentals of how we care for each other and the natural world. Indigenous cosmologies provide an alternative worthy of deeper exploration and accommodation.

Indigenous Ways of Knowing

While likely hidden from most of us, there is a quiet battle raging in modern science. The now pervasive methodologies and ideologies of modern science that can be linked back to Descartes are often quick to dismiss Indigenous or Native science for its presumed lack of objectivity. Researchers Megan Bang, Ananda Marin & Douglas Medin want us to consider whose values and knowledge systems we consider legitimate and why. The researchers call for a heterogeneity of sciences, which would value multiple systems of knowing and engage methodologies developed from other cultural communities. Speaking to critics of Indigenous ways of knowing in “If Indigenous Peoples Stand with the Sciences, Will Scientists Stand with Us?” (Daedalus, 2018), they argue for the validity of Indigenous ways of knowing:

“Skeptics of Indigenous sciences frequently assert that non-Western ways of knowing do not aim for objectivity or are incapable of achieving objective knowledge ... Indigenous sciences are no less objective than Western science ... Indigenous science operates around a set of values—as does Western science ... ‘Objectivity’ therefore cannot and should not be equated with ‘value-neutrality.’”

Shouldn’t the things we value most influence the observer’s investigations into what to observe? Striving for values-laden science based on our worldviews is desirable, not an invalidating concept of its objectivity. In Native Science Gregory Cajete emphasizes the values inherent in Tewa epistemology:

“The ultimate aim [of Indigenous knowledge] is not explaining an objectified universe, but rather learning about and understanding responsibilities and relationships and celebrating those that humans establish with the world. Native science is also about mutual reciprocity, which simply means a give-and-take relationship with the natural world, and which presupposes a responsibility to care for, sustain, and the rights of other living things, plants, animals, and place in which one lives.”

Cajete helps us to bridge the connection between what we choose to direct our attention toward and the values system that underlies those decisions. Relationality matters and a sense of responsibility can guide our knowledge gathering. By supplementing our scientific understanding with broader concepts of relationality, we affect not only what we choose to observe, but also the relevance of the implications we discover.

Relationality

Indigenous cosmologies centre on interconnectedness. In contrast to our modern, individuated culture, inquiry in Indigenous cultures is predicated on relationships between humans, plants, animals, the sun, stars, waters, and land. In the words of Lame Deer, “All of nature is in us, all of us is in nature.” Note the importance of “all” in that statement. Relative to the Cartesian duality that separates mind from body (and humans from nature and all other species), Indigenous cosmologies do not make such a distinction. Instead relationships are described in familial terms of “relatives.” In teachings shared by Black Elk with John C. Neihardt in The Sixth Grandfather, he conveyed “the first thing an Indian learns is to love each other and that they should be relative-like to the four-leggeds.” In All Our Relations: Native Struggles for Land and Life, Winona LaDuke describes those interconnected relationships between humans, other species, and nature:

“Native American teachings describe the relations all around—animals, fish, trees, and rocks—as our brothers, sisters, uncles, and grandpas ... These relations are honored in ceremony, song, story, and life that keep relations close—to buffalo, sturgeon, salmon, turtles, bears, wolves, and panthers. These are our older relatives—the ones who came before and taught us how to live.”

We can easily understand the concept of dependence and relationality with family members. But describing all parts of the natural world as familial relations is uncomfortable to the modern ear. Furthermore, establishing a relationship of dependence and reciprocity has implications for the way we should treat nature, in that same way that describing someone as family has implications in the ways we should act towards them.

In a study by Bang, Marin & Medin, they interviewed parents and grandparents from Menominee and inter-tribal urban communities to compare results with non-Indigenous parents and grandparents. The questions they asked both groups were:

“What are the five most important things for your children (or grandchildren) to learn about the biological world?” and

“What are four things that you would like your children (or grandchildren) to learn about nature?”

What they found was a stark contrast between the European American respondents and the Indigenous ones. Both groups expressed beliefs about the need to respect nature. However, the European Americans typically described nature as an external entity while the Indigenous respondents more often described creating an understanding that their children are a part of nature. Maybe you can relate to the statement, “I want my children to respect nature and know that they have a responsibility to take care of it.” As the researchers summarized, “The distinction between being a part of nature versus apart from nature reflects qualitatively different models of the biological world and the position of human beings with respect to it.”

As Robin Wall Kimmerer asks within a different context, but one that seems perfectly applicable to the results of this research, “how can we begin to move toward ecological and cultural sustainability if we cannot even imagine what the path feels like?” If we cannot find a way to build that relationality with nature and other species into our own worldview, our apartness will continue to result in damaging behaviour to the living planet.

In Land of the Spotted Eagle, Luther Standing Bear reminds us of how seemingly small, daily behaviours can help us to remember our interconnectedness with nature:

“The old people came literally to love the soil and they sat or reclined on the ground with a feeling of being close to a mothering power. It was good for the skin to touch the earth and the old people liked to remove their moccasins and walk with bare feet on the sacred earth. . . . The soil was soothing, strengthening, cleansing, and healing. . . . Wherever the Lakota went, he was with Mother Earth. No matter where he roamed by day or slept by night he was safe with her.”

It’s no coincidence that practices from yoga to mediation typically have us barefoot and in direct contact with the earth. This grounding is far more than sensory. It is a way of reminding us of that relationship that is easily forgotten in days spent walking over concrete.

Reciprocity

At the risk of sounding utterly simplistic, what if we considered the living planet and everything provided by the earth to be gifts instead of resources? This reframing changes not only our gratitude for what we have taken, but also instills a reciprocity in our feelings of responsibility to give back for what we have been given. In many ways, market mechanisms shortcut this logic. By paying for a good or service, we typically neither feel gratitude toward it nor have any responsibilities after consuming it. And so we continue to fill our homes with items of limited to zero utility with no feeling of obligation resulting from our consumption. The psychological logic goes something like, “since I worked for those wages that were used to purchase the item, it feels like a fair exchange of value.” And while currencies serve as an effective means of reducing friction between producers and consumers, they are just as efficient as undercutting our relationships of gratitude for and reciprocity to sources of production.

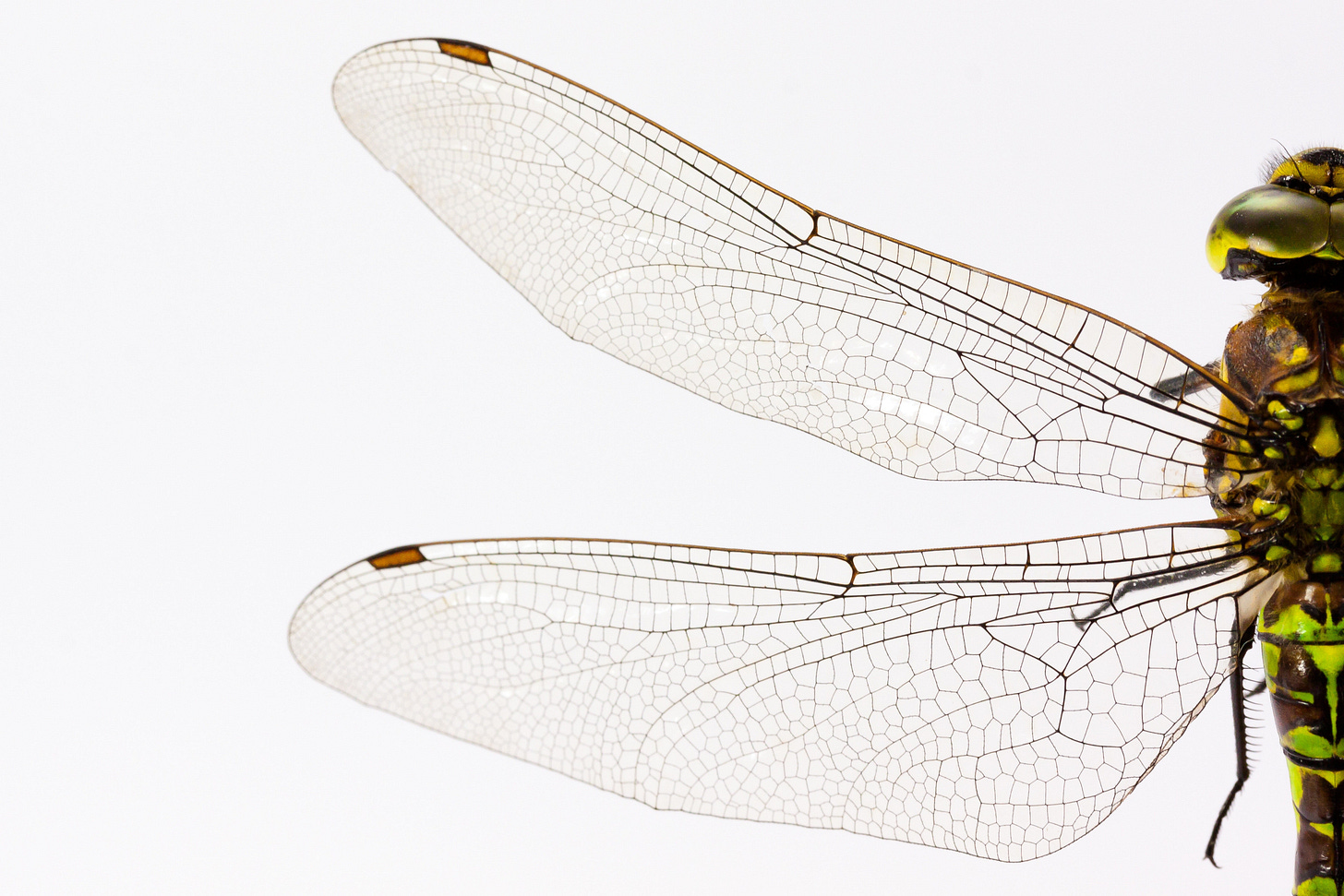

Michael Figiel, Wild Things (Shared by CC BY 2.0)

The perspective that everything is a commodity to be bought and sold is a social construct and contract that we choose to maintain. While on the surface gifts seem “free” in a market exchange context; in actuality, gift economies create a “bundle of responsibilities” through the relationships created. As Kimmerer notes in Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, the currency of a gift economy is reciprocity. Citing Lewis Hyde she shares:

“It is the cardinal difference between gift and commodity exchange that a gift establishes a feeling-bond between two people ... objects ... will remain plentiful because they are treated as gifts ... Gift exchange is the commerce of choice, for it is commerce that harmonizes with, or participates in, the process of [nature’s] increase.”

Kimmerer likes to say that she was raised by strawberries, fields of them. Through her discovery and cultivation of wild strawberries as a child, she embraced a worldview of gifts from the earth. “The field gave to us, we gave to my dad, and we tried to give back to the strawberries.” By what she had been given, Kimmerer felt responsible to receive and to reciprocate.

As I’ve spent more time with Indigenous writing and storytelling, I notice how often it is punctuated by pauses of gratitude for the gifts we have been given. Kimmerer is grateful to the strawberries. Winona LaDuke and Black Elk are grateful for the teachings learned from the “four-leggeds.” Imagine just how radical a transformation it would be if we all felt an overwhelming love and thankfulness for a strawberry! The feeling of pervasive gratitude would shift our feelings of interconnectedness with nature, as well as how we go about our daily lives protecting or harming it. The Medicine Man of the Lakota tribe, Lame Deer, succinctly summed up the broader implications of increased relationality and reciprocity in our lives, "Because we . . . also know that, being a living part of the earth, we cannot harm any part of her without hurting ourselves." Harming the living planet would be acknowledged as self-inflicted harm.

Towards a New Operating Worldview

I promised that this issue would not just propose theoretical alternatives, but could help to reshape our worldview that influences daily behaviour. Relative to the checklist of Eisenstein which proposes policy shifts without the broader epistemological shifts we’ve been discussing, Bang, Martin & Medin provide more instructive guidance in how we scale scientific pursuits on the relational epistemologies of Indigenous science. In effect, they seek to cancel out the separations Descartes and his descendants created over three hundred years ago that still endure today:

View humans as a part of the natural world, rather than apart from it;

Attend to and value the interdependencies that compose the natural world;

Attend to the roles actors play in expanded notions of ecosystems from assumptions of contribution and purpose, rather than assumptions of competition;

Focus on whole organisms and systems at the macroscopic level of human perception (also a signature of complex-systems theory);

See all life forms as agentic, having personhood and communicative capacity (as distinct from anthropocentrism);

Adopt multiple perspectives, including interspecies perspectives, in thought and action; and

Weigh the impacts and responsibilities of knowledge toward action.

While you might have felt yourself nodding your head in agreement with most or all of these statements, embracing them would entail a radical shift in how we approach our lives and ways of understanding our connectedness to each other and nature. But in many ways, they also feel like common sense. So how is it that something that seems like common sense can be so radical at the same time? The answer lies in the brokenness of the system that we openly acknowledged at the beginning of this issue. Instead of tightening the screws on a broken machine, we should be rethinking how we change our perspective of it altogether. At the core of that reconceiving are the values that we cherish. Separating values from ways of knowing is not just bad science, it is also irresponsible and one of the culprits for the current state we find ourselves in today.

Conclusion

Indigenous science or ways of knowing provide a fundamental restructuring of how we view nature and our relationships to it and other species. Kimmerer describes this reframing as taking care of the land “as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it.” By viewing everything as interconnected and relational, we find not only a greater gratitude for all that we have in our lives, but may also act more responsibly in how we treat the gifts we’ve been given. In embracing markets as a form of exchange, we have nearly entirely lost the cultures of reciprocity that once dominated our responsibilities for each other, other species, and nature more broadly. But as the many writers in this issue remind us, the worldview(s) we live with is a choice. If we choose to perceive the world as a gift, we will treat it respectfully. As Kimmerer notes, “when we view the world this way, strawberries and humans alike are transformed.”

Go forth and make a difference in the week ahead.

Adam

In between issues I share my own reflections and those I have heard from readers. While the term community is often overused and thus abused, The Understory is a community of readers who value the comments of others. Please reply to this email or leave a comment on the website with any reflections you feel comfortable sharing 🙏.

In addition to reading the works cited above, I would also recommend listening to the wise voices of Robin Wall Kimmerer with Krista Tippett on The Intelligence in All Kinds of Life, and Miles Richardson, O.C., Dr. David Suzuki, Dr. Nancy Turner, Elder Dr. Dave Courchene, Jr. and Valerie Courtois on Why Reconciling Ways of Knowing?

As I reached the section in which you refer to Cartesian thought, I reflected on how the discovery of the atom further emphasized the ideas of separation and mechanization and disconnected us from the processes that make life possible. I wish I could remember whose book I read, but the assertion was that studying phenomena at a microscopic level not only fills our minds with facts and details, obscuring the bigger picture, it also encourages us to separate phenomena into their individual parts, almost dissecting them as Descartes did to animals to prove they had no soul. We ending know more and understanding less.

On a hokier level, your appeal to indigenous cultures reminds me of the analogy in Daniel Quinn's New Age novel Ishmael. In it, Ishmael asks the narrator to consider his society as a a car driven off a cliff and to imagine how many cars have already crashed at the bottom. He then points out that there are plenty of societies that have simply chosen not to drive off the cliff. In our current society, it seems that the best we can do is rearrange deck chairs on the Titanic (sorry to mix my metaphors). I'm still vegetarian 25 years later, and this makes me healthier and reduces my carbon footprint, has some infinitesimal effect on factory farmed animals, and has some similarly small effect on slash-and-burn agricultural, but does it really have any effect on the direction our society is headed? No, not really. Does that or should that reality compel me to change my behavior? I don't think so. I continue to believe that such decisions have intrinsic value, if only because I have thought them through and continue to challenge myself on that value.

Thanks for pulling all this together Adam. Where do you find time to do all that reading??!

I think many of us get the interdependent, interconnected world model. eg. I think of the David Suzuki Foundation's (new) vision: "that we all act every day on the understanding that we are one with nature."

The big challenge as I see it is shifting a critical mass of human behaviour to that understanding, from linear/detached to circular/interdependent. Certainly current trends to mindfulness, slow streets/food/growth, ongoing spiritual voyages are bright spots. Urgently. All over the earth.

But alas those who practice such living have historically been dominated, exploited, destroyed and impoverished by prevailing capitalist and colonialist drivers. When I read how the domination gene can now be supercharged with surveillance AI, I shudder for the ability of evil dominants (confession: I too live off the avails of historical conquests of this type) to rise to even greater heights as they bring us all down.

All that said, COVID may be our friend. It shows no mercy to those who insist the economy trumps everything; it fractures a lot of the structures that our doom is built on, and it reveals our utter interdependence with the smallest of beings almost completely beyond our control. It is also powerful enough to really get our attention.