I’m pleased you found The Understory—my biweekly essays with critical perspectives on climate change. If you’re here for the first time, hello! Enter your email below to get issues to your inbox, free.

“I beg you, to have patience with everything unresolved in your heart and to try to love the questions themselves as if they were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.”

Rainer Maria Rilke, Letters to a Young Poet

Over the next couple of weeks, many of us find the space to slow the pace of our lives. And it is no coincidence that this period also represents a time of introspection—when we cast forward into the next year to consider the possibilities that may emerge ahead. It is an opportunity for us to accept Rilke’s invitation to live the questions rather than their answers.

What is the space between desire and intention? Between intention and practice? Between practice and transformation? Recognizing that for many of us the calendrical new year is a temporal landmark of change, I thought it was fitting for the last issue of 2020 to explore how introspection leads to lasting resolutions. To explore why we make resolutions each year despite the subconscious recognition that most of our intentions will never materialize. Between 40-50% of adult Americans (at least) create New Year’s resolutions, with varying reports of goal attainment ranging from 46% to only 4%.

The human mind seems naturally drawn to temporal landmarks, and often imbues them with meaning: birthdays, New Year’s, and various cultural rites of passage through ceremony when people reach certain ages. It is in such temporal moments as the coming new year that we create the space to consider what was, what is, and what can be. I hope I can encourage you to be even more courageous this year in setting your resolutions—to move beyond the self and even our immediate circles to consider our respective roles in bringing about a healthier planet and more reciprocal relationships with others in the year to come.

Begin Again, Again

In December many of us return to ask ourselves what we should resolve to do, to support, and to become next year. Within Western culture, these resolutions often correlate to our worldview that time is a march of progress. As we grow older, our cultural logic of achievement casts greater expectations on what we expect of ourselves. New habits are vessels for improvement, and where many of us direct our intentions as the calendar year turns from one year to the next.

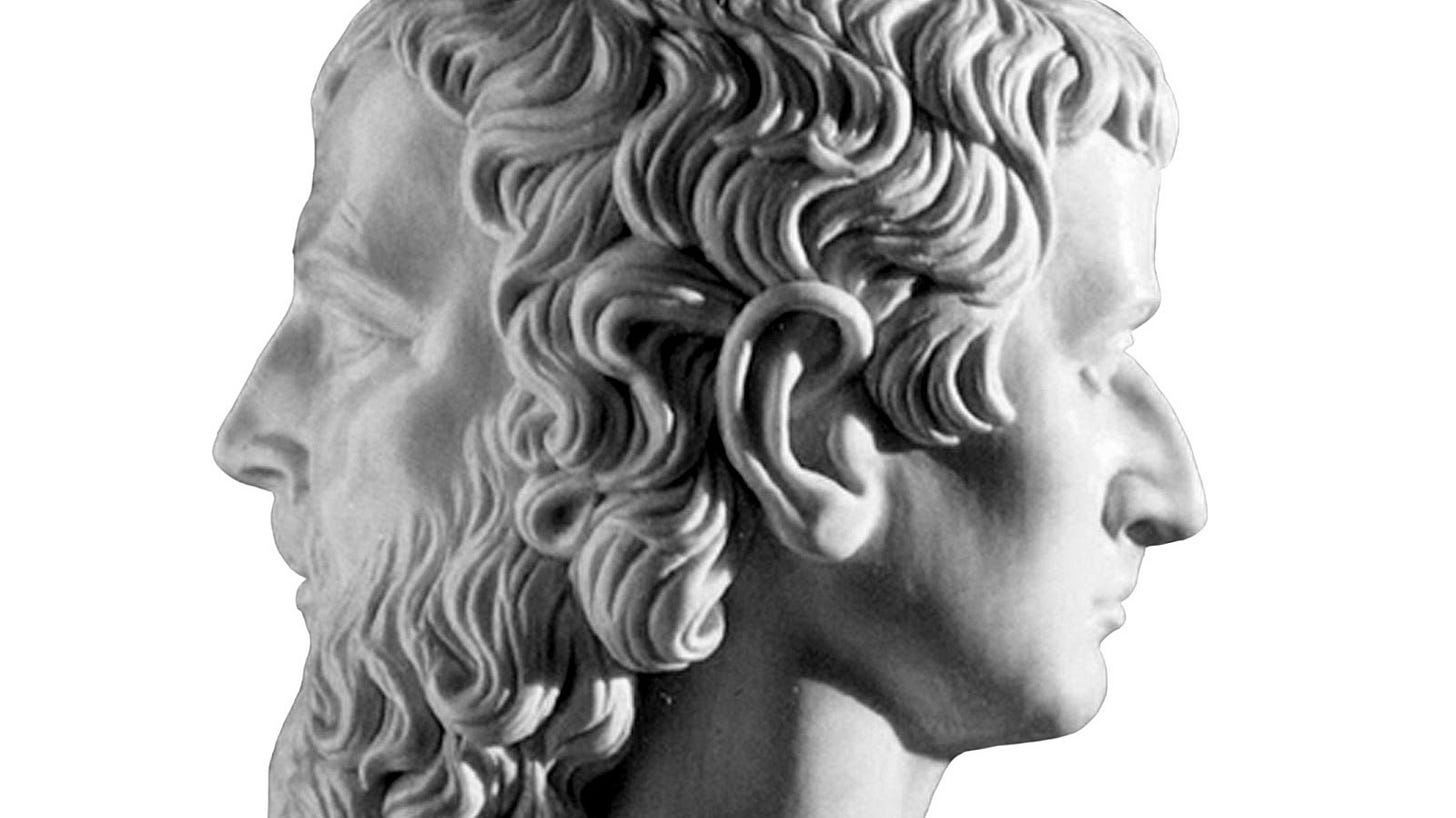

Frederick Nietzsche was at least partially at odds with this cultural logic of temporal progress. Writing in The Gay Science (1882), Nietzsche espouses the benefits of “brief habits,” while loathing “enduring habits.” Brief habits are the gateway to knowing many things, but he willingly releases those habits with the same grace that they were originally embraced: “as if we had reason to be grateful to each other as we shook hands to say farewell.” On the other hand, enduring habits feel oppressive to Nietzsche: “as if a tyrant had come near me and as if the air I breathe had thickened.” A life devoid of habits is intolerable as it requires perpetual improvisation. But habits should never become enduring so as to lose their lustre and become limiting rather than expansive forces in our lives.

While Nietzsche reflected a nuanced view of temporal progress, Benjamin Franklin was a cultural progenitor of the emerging American notion of continuous progress. Franklin celebrated rather than felt oppressed by the cultivation of new, enduring virtues. In The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (1791), Franklin wrote:

“It was about this time I conceived the bold and arduous project of arriving at moral perfection. I wished to live without committing any fault at any time; I would conquer all that either natural inclination, custom, or company might lead me into.”

Franklin recognized that intention in being completely virtuous alone was not sufficient to prevent slippage. He needed to break long-standing habits and acquire better ones. After completing his catalogue of thirteen moral virtues—Temperance, Silence, Order, Resolution, Frugality, Industry, Sincerity, Justice, Moderation, Cleanliness, Tranquility, Chastity, Humility—Franklin

“made a little book, in which I allotted a page for each of the virtues. I ruled each page with red ink, so as to have seven columns, one for each day of the week, marking each column with a letter for the day. I crossed these columns with thirteen red lines, marking the beginning of each line with the first letter of one of the virtues, on which line, and in its proper column, I might mark, by a little black spot, every fault I found upon examination to have been committed respecting that virtue upon that day.”

Franklin chose to “master” one virtue at a time before proceeding to the next. He gave himself a “week’s strict attention” to each of the virtues. Over time, supposedly, he cumulatively acquired the “habitude” of all thirteen virtues.

While Franklin’s process is one of legend in personal betterment circles, I suspect the research of Peter Gollwitzer on the relationship between intention and goal realization holds greater promise for most people. Gollwitzer determines two primary fail points in the path to goal attainment. First, is the failure to start, which can be broken down into constituent parts: remembering to act, seizing the opportune moment to act, and second thoughts at the critical moment. Gollwitzer identifies that for many of us, we forget to find the space to implement changed behaviours or miss the right moments entirely when they present themselves. Second, is derailment along the way towards goal attainment. Often our resolutions demand recurring behaviours, giving each of us ample space to fall down on the path towards attainment. Gollwitzer lists three particular derailing moments: being enticed by stimuli, avoiding ingrained habits that are contrary to our goals, and the overwhelm that we often experience when we find ourselves in negative states. “Implementation Intentions: Strong Effects of Simple Plans” (1999) shows just how hard it is to attain our resolutions, and equips us with processes for increasing our likelihood of success.

In his theory of implementation intentions, Gollwitzer recognizes the significance and myriad possibilities for misdirection and offers a structure that encourages the planning for contingencies in advance of confronting them. He suggests we have an automatic response for each continency in the moment in which they arise. Instead of the way we typically structure resolutions—“I intend to achieve X”—Gollwitzer encourages a situational context paired with our intention. By creating an “if-then” construct, we create a relationship between behaviour and when, where, and how we will do it. This interlinking can help us to overcome many of the self-regulatory problems that undermine our resolutions and derail the formation of new habits.

No Regrets

For many of us, the process of creating resolutions is as much about reflecting on regrets as it is about imagining different future possibilities. In the beginning of Book Four of The Gay Science, “Sanctus Januarius,” Nietzsche shares a concept that became one of his prevailing approaches to life in coming years, “amor fati,” the Latin expression translated as “a love of one’s fate”:

"For the new year—I still live, I still think: I still have to live, for I still have to think. Sum, ergo cogito: cogito, ergo sum. Today everybody permits himself the expression of his wish and his dearest thought; hence I, too, shall say what it is that I wish from myself today, and what was the first thought to run across my heart this year—what thought shall be for me the reason, warranty, and sweetness of my life henceforth. I want to learn more and more to see as beautiful what is necessary in things; then I shall be one of those who make things beautiful. Amor fati: let that be my love henceforth! I do not want to wage war against what is ugly. I do not want to accuse; I do not even want to accuse those who accuse. Looking away shall be my only negation. And all in all and on the whole: some day I wish to be only a Yes-sayer."

Nietzsche begins the new year with a reflection on Descartes’ cogito, ergo sum: “I am, therefore I think: I think, therefore I am,” recognizing that a new year represents a new beginning, but also the eternal process that makes us most human—our ability to think. And with that ability to think comes the capacity to envision a different future for ourselves and others. Nietzsche’s resolution of “amor fati” is a recognition that the ability to love everything is one of life’s greatest virtues. The goal attainment for Nietzsche’s New Year’s resolution is to comfortably exist as a “Yes-sayer” through cultivating the ability to accept everything that comes.

Nietzsche recognizes the ongoing struggle within himself to dwell on regret, and how destructive of a force it can be in our lives. But Nietzsche does not call for us to negate these events in constructing personal narratives of improvement and progress. Rather, he wants to actively accept the errors, injustices, and ugliness in our lives along with the good and the wise. To stop fighting against negative events. Later in Book Four, “284—Faith in oneself,” Nietzsche laments that many of us fight the skeptic within ourselves, which is at the root of “great self-dissatisfied people.” The ability to overcome the skeptic within “almost requires genius.”

Rather than advocating for resignation, Nietzsche saw “amor fati” as a way of willing a richer life into being:

“At the height of the mood of amor fati, we recognise that things really could not have been otherwise, because everything we are and have done is bound closely together in a web of consequences that began with our birth—and which we are powerless to alter at will. We see that what went right and what went horribly wrong are as one, and we commit ourselves to accepting both, to no longer destructively hoping that things could have been otherwise. We were headed to a degree of catastrophe from the start. We know why we are the desperately imperfect beings we are; and why we had to mess things up as badly as we did. We end up saying, with tears in which there mingle grief and a sort of ecstasy, a large yes to the whole of life, in its absolute horror and occasional moments of awesome beauty.”

The School of Life, “Nietzsche, Regret and Amor Fati”

Nietzsche invites us to say “yes” as an uncompromising act of accepting reality (see Issue Thirteen). Once we accept that our lives are composed of a series of imperfect events, we can embrace those imperfections to more easily accept them as they continue to arise. And with this acceptance comes the ability to see beyond—to create a continuous resolution of sorts that is inclusive of everything we are and have been as we cast ourselves forward into an unknown future.

Go Easy On Your Selves

Over the course of a lifetime, each of us has multitudinous versions of self. Given the season and that the forthcoming researchers cited it, I think it is fair game to evoke the parable of Ebenezer Scrooge from Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol to demonstrate the concept of multiple selves. An individual who most would deem morally reprehensible, Scrooge finds himself visited by three ghosts on Christmas Eve who expose him to his past, present, and future selves. Based on the ability to see these multiple selves, Scrooge awakens on Christmas morning a changed man and seeks to derail the future self he witnessed while repairing his behaviours of the past declaring: “I will live in the Past, the Present, and the Future. The Spirits of all Three shall strive within me.”

While it is unlikely we will be visited by similar ghosts, temporal self-appraisals such as the creation of a New Year’s resolution serve as moments when we consider our present self in contrast to past selves and desired future ones. In “From chump to champ: People's appraisals of their earlier and present selves” (2001), researchers Anne E. Wilson and Michael Ross wrote that our past selves are “akin to an interconnected chain of different individuals who vary in closeness to the current self.” On purely rational terms, the idea that we embody a different self from one day to the next just because of a calendrical sleight of hand seems preposterous. And yet, temporal events enmeshed with our cultural theories of progress can yield strong psychological forces. Those forces can manifest the transformation into a new self with the corresponding flip of our calendars (I realize this dates me to the time when we hung physical calendars on a wall).

Wilson and Ross found that we are motivated to praise our psychologically recent past and future selves and to criticize our distant selves to feel good about the present. As a kind of salve to the cultural unhappiness of Western society, they offer that if we are willing to retrospectively exaggerate an unhappiness in our past, it can create greater happiness with the present. In other words, throw our past selves under the bus as a sacrifice for our present selves even if no real change is apparent. Wilson and Ross call this temporal self-appraisal theory (TSA) wherein peoples’ evaluation of a past or future self largely depends on how close that self is to the present day, both literally and by the attributes that we most value. Individuals selectively recall evidence of improvement and ignore indications of decline. Wilson and Ross write:

"Just as advertisers creatively manipulate evidence to showcase constantly ‘new and improved’ products, so too might individuals repackage and revise themselves to highlight improvement on important dimensions.”

Of particular significance to our understanding about resolutions is Wilson and Erin Strahan’s findings about the relationship between proximity to our future selves and the impact on our current motivation to achieve goals (“Temporal comparisons and motivation,” 2006). They found that “a future possible self which feels psychologically close is more motivating than a future possible self which feels psychologically distant.” When applied to our ongoing discussion about climate action, the implications are significant. While we already see the effects of climate change with species extinction, wildfires, forced migration, hurricanes, ocean acidification, and other catastrophic events, most of the conversation about the climate emergency suggests the most dramatic effects are in the distant future. While these effects may be exponentially larger in scale than the ones in our near future, the research of Wilson and Strahan demonstrates that our introspection, communication, and visualization should be focused on close future effects, as nearness has the strongest impact on current motivation. Envisioning possible future selves can motivate our current selves, but they must be psychologically close to our present selves.

While temporal self-appraisal theory focuses on self-motivation, I was encouraged to discover the research of Benjamin Houltberg and Arianna Uhalde from USC’s Performance Science Institute who found that moving beyond the self in our resolutions will increase our likelihood of keeping them. In their article “How putting purpose into your New Year’s resolutions can bring meaning and results,” Houltberg & Uhalde encourage us to reframe our resolutions around “purpose-based performance,” moving from outcome-driven resolutions to collective ones. They suggest three questions to ask yourself:

What are my longer-term goals?

Why is this personally important?

Who will be positively affected by this?

Each of these answers should be contextually framed as resolutions in the larger communities and systems that we hope to impact. Perhaps this is the greatest insight of them all. What we resolve is both more important and more likely to be attained if our resolutions are centred on their relationship to the world around us. By reconceiving our resolutions as relational, we, like Nietzsche, may become one of those who make things beautiful in the year ahead.

Conclusion

A New Year’s resolution can be thought of as an annual psychological experiment in how we consider our selves in relationship to time. For many of us, temporal landmarks effectively serve as both the mental construct as well as the actual seed of transformations from one self to the next. While we might have difficulty identifying these discrete selves in our current moment, the psychological constructs of our past and possible future selves are subconsciously used to evaluate our current self. The closer a future self feels psychologically, the more motivating it becomes for us to strive to attain it.

In our moments of introspection, Nietzsche asks us to resist the temptation to regret and retouch the past. Our past and possible futures are not selves to choose between, but rather multiple selves to accept. To strive like Nietzsche to be a “Yes-sayer.” While resolutions often centre on the self, we are reminded to ground them in a larger purpose for the world we desire to bring forth. This not only creates a greater likelihood for goal attainment but also creates relationships with others around us. It is perhaps in the strengthening of these relationships to all living things—humans, animals, plants, rocks, water, fire, air—that we might find the most meaningful resolutions of all.

Go forth and make a difference in the year ahead.

Adam

In between issues I share my own reflections and those I have heard from readers. While the term community is often overused and thus abused, The Understory is a community of readers who value the comments of others. Please reply to this email or leave a comment on the website with any reflections you feel comfortable sharing 🙏.

If you liked this issue, please subscribe. The Understory is free and will come to your inbox weekly.

Why I Write The Understory

We have crossed the climate-change threshold from emerging to urgent, which demands a transformative response. The scale of the issue demands not only continuous focus but also the courage to take bold action. I've found that a persistence of climate consciousness improves resilience to the noise and distractions of daily life in service of a bigger (and most of the time invisible) long-term cause.

The Understory is my way of organizing the natural and human-made curiosities that capture my attention. Within the words, research, and actions of others lies the inspiration for personal and organizational journeys. I hope that my work here will help to inform not just my persistent consciousness, but yours as well.

Thanks for this wonderful end-of-year meditation and invitation to capacity building.

One this part: "But habits should never become enduring so as to lose their lustre and become limiting rather than expansive forces in our lives." I see these sort of like whale songs, we can slowly shift our practices over time as needed to keep them appropriate to our needs. Somatics talks about an ever expanding spiral of human development that is based on understanding what we are currently practicing, and what we need to practice instead to grow into the shape we seek to become. We study our current habits, and then shift them over time. This means that later, our relatively newer habits are the ones that are again studied, and then shifted to what is needed next. Habits grow branches, some are pruned back, but the tree of our lives becomes larger and healthier over time.

Regarding “I intend to achieve X”—Gollwitzer, we get into the research of Richard Boyatzis et. al. on the shift from what he and his colleagues term "coaching for compliance" versus their coined approach "coaching from compassion" or "Intentional Change Theory." Which is to get out of our task-positive neural network (near term accomplishments, goals, judgements, closed mindset) to the default mode network (tend & befriend, forward-focus, open mindset). We do this by as both Gollwitzer, Boyatzis and Covey would say -- beginning with the vision of the bright attractive future ("begin with the end in mind"). Their research shows 65-85% efficacy of keeping the attention on this "positive emotional attractor" of our future visioin vs. 11% success rate or worse that comes from focusing only on consequences, "should" or what they term "negative emotional attractors". The three questions from TSA help here by focusing on positive outcomes.

Furthermore on Temporal Self Assessment Theory - backward-looking self assessment can become its own cul-de-sac. For instance spending decades rehashing our past in whatever modes of disbelief, self-blame, shame, judgement, regret, etc. By contrast, Buddhism holds there is no fixed identity, and every moment (and we in it) are fresh and new -- which both gives us the freedom to unlock our own mental/emotional cages while also handing us the radical responsibility to constantly reassess our assumptions, or simply practice setting our assumptions aside so that we may rise to whatever the present moment calls for in terms of response from us.

Amor fati is not only Nietzche's but also the saying of the Stoics - here he has a more positive bent to his appreciation of life - but from the stoics' standpoint it was to love *every* aspect, not just the beautiful; their discipline including somehow coming to love our dire hardships (the seemingly crueller side of our fate, was stripped of judgement and more than simply endured). What Buddhism would call equanimity. This is like Rabia al Basri's wonderful "I was born, when all I once feared, I could love." May we all reach such peace, and then act from it for the sake of the planet this coming year and all the years hence.

This is a great piece to put some perspective on new year resolutions. I can personally attest to the improved results of applying Houltberg and Uhalde's three questions to one's resolutions, even though I of course never knew anything about their theories at the time. I think we all apply the first question of hoping that our resolutions will meet our long term goals, and indeed most of us probably approach resolutions from a personal standpoint, but my own enlightenment comes from the third question which is to consider who else in this big wide deserving world might be positively affected by my own resolves and actions. Excellent.

Thanks Adam !